There was a bit of hesitation from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist Stephanie C. Herring when she was asked questions about the increased risk and the implications of that risk for the insurance industry posed by climate change.

Hesitation from people discussing their insight into climate change typically centers around whether it’s human-caused.

Neither risk nor the insurance world are in Herring’s field, and she said as much. However, when she was told how relevant extreme weather was to the insurance community, the floodgates to her thoughts on climate change and risk opened wide.

“The climate is changing because of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions and there are extreme events that are changing because of those greenhouse gas emissions,” said Herring, lead editor Explaining Extreme Vents of 2014 from a Climate Perspective.

The report out recently from NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center is based on attribution science.

Attribution science, the report states, attempts to answer a number of tough questions, including: “Can climate change influences on single events be reliably determined given that observations of extremes are limited and implications of model biases for establishing the causes of those events are poorly understood?”

The scientific developments detailed in the 172-page report – an annual compilation of reports that has been released for the past four years – along with broader scientific literature suggest that event attribution that detects the effects of long-term change on extreme events is possible.

“However, because of the fundamentally mixed nature of anthropogenic and natural climate variability, as well as technical challenges and methodological uncertainties, results are necessarily probabilistic and not deterministic,” the report states. “As the science advances, other questions are emerging. For what types of events can event attribution provide scientifically robust explanations of causes? Is near-real-time attribution possible? And, how useful are science-based explanations of extremes for society? We consider these questions in more detail.”

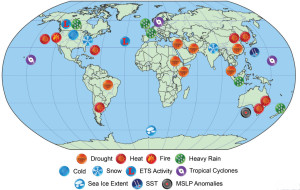

The paper is the sum of 33 different research groups exploring the causes of 29 different events in 2014.

According to Herring, some weather perils outlined in the report offered clearer signals they could be tied to climate change.

The severe wildfire year for California, while not directly linked to climate change, is likely a result of a prolonged drought, which authors of the paper believe is a result of global warming.

“The fire season in Northern California during 2014 was the second largest in terms of burned areas since 1996. An increase in fire risk in California is attributable to human-induced climate change,” the report states.

This year was a pretty rough one as well for wildfires in the northern half of the state. Just two fires, considered among the state’s largest, are expected to yield claims in excess of $1 billion.

Herring explained that drought is a function of heat, lack of precipitation, soil moisture and water usage. Not all of those factors are attributable to climate change, but she feels confident that the warmer temperatures that California is experiencing are being driven by climate change.

“There’s a very clear signal that climate change is increasing our risk at a global scale to heat events,” Herring said.

The past four years’ worth of papers have looked at forests from around the world, including South American, Asia, and Australia, and 95 percent of the trees examined have shown a strong climate change signal, she said.

While heat events can be most confidently tied to climate change, not all weather perils come with such clear signals, Herring said.

For example, the tropical cyclones that struck the Hawaiian Islands in 2014 aren’t so easily attributable to climate change.

According to a section of the report titled “Investigating The Influence Of Anthropogenic Forcing And Natural Variability On The 2014 Hawaiian Hurricane Season,” where the term “Anthropogenic Forcing” in regular-speak translates to “manmade,” there is some indication climate change may be involved.

But El Niño, which has been developing for some time, is also a strongly suggested to a culprit.

“New climate simulations suggest that the extremely active 2014 Hawaiian hurricane season was made substantially more likely by anthropogenic forcing, but that natural variability of El Niño was also partially involved,” the paper states.

The paper notes that three hurricanes approached the Hawaiian Islands during the 2014 hurricane season, which is the third largest number since 1949.

Previous studies suggest that the frequency of tropical cyclones around Hawaii are expected to increase under global warming, but natural variability, such as that associated with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, also has a significant influence on tropical cyclones activity near Hawaii, the paper states.

“There’s still a lot of research that needs to be done to understand how tropical cyclone risk is changing because of climate change,” Herring said. “We’re not always going to find a fingerprint at the crime scene.”

Past columns: