A whopper of a winter appears to be brewing for the Western U.S. and more conversations are turning to preparations for what could be one of the strongest El Nin᷈os on record.

Strong rains throughout much of California and snow in the mountains earlier this month – the first significant moisture to hit many parts of the state after four years of persistent drought – are being followed by fierce winds this week.

A tornado was reported on Monday in the central part of the state, while powerful gusts caused power outages around Southern California. Wind speeds around Los Angeles in excess of 30 mph were recorded, with gusts up to 70 mph.

Even skeptics may have a hard time denying that this now appears to be an official El Nin᷈o.

Rod Harden, head of catastrophe claims at Farmers Insurance, is taking the El Nin᷈o talk seriously, especially after weather forecasters began comparing this year’s weather phenomenon with the 1997-98 El Nin᷈o. That was the strongest El Nin᷈o recorded.

“We’ve been doing a lot of looking back at the 97-98 event,” Harden said.

Farmers is examining where its policies are in force and then using computer models to overlay those areas onto maps showing where the storm damage was most severe in the 97-98 event, he said.

Harden is committing resources to such endeavors because he believes this year poses some added threats if the storms are as severe as some fear.

“If this were a 97-98 type of event, there will be widespread flash flooding,” he said. “This could be even worse because of the drought.”

The Western U.S., and California in particular, is expected to bear the brunt of the El Nin᷈o-driven storms. Four long years of drought left a lot of dried ground in California. It’s ground that will take time to receive large amounts of rain, making heavy runoff likely.

This effect may be compounded by the numerous burn scars from this year’s severe wildfires in Northern California, which eliminated vegetation and left areas further exposed to flash flooding and mudslides, Harden said.

If this sounds like a lot of “ifs,” Harden has a solid basis for his concerns.

“I think we are looking at an event similar to the 97-98 event if the meteorologists have it correct, and I think they might,” Harden said.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has been talking about an El Nin᷈o with growing confidence since early last year.

Tom Di Liberto, a meteorologist at the NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, believes this could be one of the strongest El Niños since weather watchers began tracking the phenomenon in the 1950s.

“I would say that we’re currently in a strong event,” Di Liberto added.

He’s giving good odds it will rank up there with the two strongest El Niños on record.

NOAA recordkeeping for El Niños dates to 1950. The 97-98 event is the strongest on record, followed by the 1981-82 El Nin᷈o, according to Di Liberto.

“We expect it to peak at a top 3 level,” Di Liberto said of this year’s El Nin᷈o.

The brunt of the impact is expected in November, December and January, so these are about to be tested.

“We’re getting close to when we expect this event to peak in strength,” Di Liberto said.

Like the 97-98 event, he said to expect heavy rainfall, winds and landslides and mudslides exacerbated by flash flooding.

“Concern is there that his could lead to another round of landslides and mudslides,” Di Liberto said.

Statistics from the Federal Emergency Management Administration show that since 1978 the two strongest El Nin᷈os on record produced a significant share of the flood claims in the National Flood Insurance Program.

FEMA blames the El Niño years of 1982/83 and 1997/98 for 11,501 out of California’s total 30,751 (37.4 percent) paid NFIP claims during the past 37 years.

“Flooding can happen any time, but there is even greater risk in El Niño years,” Susan Hendrick, a FEMA spokeswoman commented in an email explaining these statistics.

Researchers at the Insurance Information Institute came up with some interesting stats on the two largest El Nin᷈os.

The I.I.I. stats show:

Catastrophe modelers are cautioning their insurance clients to be prepared, yet they are also cautioning against overreaction.

“The caution that we advise is that these are really strong signals,” said Tom Larsen, senior vice president and product architect at CoreLogic EQECAT.

However, these weather patterns don’t always turn out to be as advertised, he added.

He has been giving clients details on expected type of losses – with winter weather impacts ranging from normal to worse – but with weather forecasts out past 30 days the accuracy becomes far less reliable, he said.

Even with his level-headed approach about reacting to weather events that may be months off, Larsen acknowledges that most signs point to erring on the side of caution.

“It’s certainly not going to be an average year,” Larsen said.

What are his clients doing?

“Many of them are reviewing procedures of what they’ve done in the past,” Larsen said. “These storm years (97-98, 81-82) were very disruptive, but they were very survivable. We have to cautiously anticipate these losses and events.”

Clients want to know when there is greater certainty in the forecast just how bad they can expect it to get, he said.

“They’re waiting much as we are, but when there is greater certainty what the losses could be, they’re looking for advice with what regions could be impacted and how bad it could be,” he said. “The kind off storms that we talk about are what we call the pineapple express storms that are associated with great winds and very heavy rainfall. Property damage will not just be related to water damage, but it will also be related to tree falls.”

Roof collapses are another concern. Many roofs in California, where severe storms are far and few in between in most years, are often not well maintained, and roof drains are often left clogged, he said.

“So there will be those types of collapses,” Larsen added.

Peter Sousounis, assistant vice president at AIR Worldwide, shares Larsen’s caution against overreacting, but he too acknowledged that it’s shaping up to be a very strong El Nin᷈o.

“The current El Nin᷈o is quite strong and from an intensity standpoint will likely fall somewhere between the 82-83 one and the 97-98 one,” Sousounis stated via email. “However, it does not mean that our weather will be similar to what we experienced in either of those other two events and not necessarily for the entire winter season.”

For one, every El Nin᷈o event is different, he said.

“For another, where the strongest warm-water anomaly is located in the Pacific can make a big difference,” Sousounis added. “An eastern Pacific El Nin᷈o is what happened in 1982-83 and 1997-98. That means that the strongest anomaly was located in the eastern Pacific – along the coast of South America.”

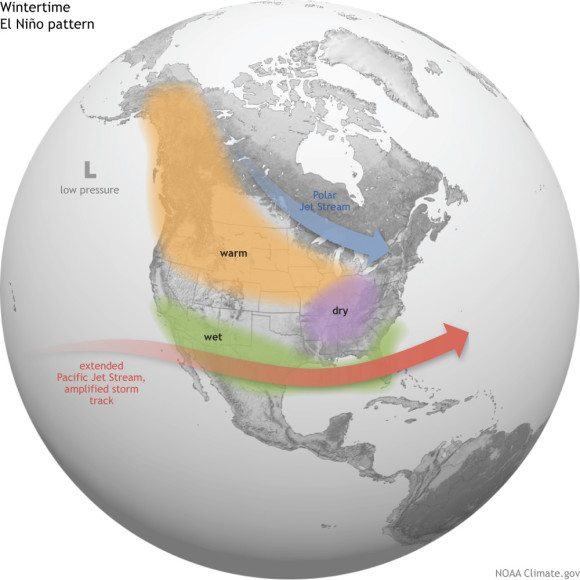

The expected impacts on the U.S. from an Eastern Pacific El Nin᷈o are mild and primarily dry weather across the Northern tier of states with the greatest impact occurring in the northern Great Plains and Midwest, he said.

Across the southern tier of states, the weather is typically wetter and cooler than normal, he added.

“In terms of big storms and where they would occur – definitely in Southern California,” Sousounis said.

Heavy rainstorms in California would translate into big snowstorms for the Southern Rockies, while farther east along the Gulf Coast and extending into Florida severe thunderstorms will be more likely, according to Sousounis.

Farther north, along the Mid-Atlantic states and into New England and Canada, there can still be significant storms with wintry precipitation, he added.

“Remember Canada’s biggest ice storm and biggest insured loss? That happened during the winter of 1997-98 (January 1998 – the North American Ice Storm of 1998),” he said.

Is the insurance industry prepared for all of this?

The man perhaps best situated to tackle that question is Robert Hartwig, president of the I.I.I.

Hartwig said the industry typically comes out of El Niños with both losses and gains.

“They tend to be associated with weather events that, while they can increase losses in some parts of the country, they may produce lower losses on other parts of the country,” Hartwig said. “So there can be partial offsets.”

He added, “They are events of a magnitude that insurers can certainly manage.”

He is fairly bullish on how the insurance industry will fare this year from these expected storms, but the head of I.I.I. wasn’t so high on how Californians are prepared to withstand flood losses.

California has the 4th highest number of flood policies in force in the U.S. As of end of 2013, there were 246,000 policies in force in the state. Fourth highest doesn’t sound so bad. But California is the nation’s most populous state.

By comparison, Florida had 2 million flood policies in force, Texas had 627,000 and Louisiana had 480,000. So California’s fourth ranking speaks to a problem with flood policy penetration in Hartwig’s view.

“It’s clearly far below theses states and it’s below other states,” he said of California’s penetration.

I.I.I., FEMA and the California Department of Insurance have been among the numerous voices warning California homeowners to buy flood insurance now, because it takes 30 days for a policy to be in effect.

Hartwig, based on past history, believes all the warnings in the world are as effective as effective as floods themselves, of which California has had few in the past decade.

“The reality is nothing sells flood coverage like an actual flood,” Hartwig said. “Unless there are major floods, the needle on flood purchases won’t move that much.”

It’s not just California that’s an insurance buying loafer. Globally, a lot of the world is uninsured.

“Underinsurance is a very significant problem globally and also right here in the United States,” Hartwig said.

He noted that flood risks are the most uninsured and underinsured. A recent I.I.I. poll shows roughly 14 percent of U.S. homeowners have flood coverage.

There has been a 9.6 percent reduction in NFIP policies in-force since 2009, which equates to 550,000 polices fewer in the past six years, according to Hartwig.

“This is occurring despite surges in coastal development,” Hartwig added. “It’s troubling because what we see is, we know that there will be large-scale flooding events costal or otherwise and what this suggests is less people will be protected from flood loss.”

Flooding isn’t the only peril that Harden with Farmers associates with El Niño.

“Flood is just one of the many things you’ll see as a result of a deluge of rain,” he said. “Mudslides have the potential of concurrent causation where coverage could be afforded as a result.”

He added, “We’re always looking to afford coverage.”

His list of possibilities include: Trees being blown down onto structures; shingles blown off roofs and creating an opening that can result interior water damage; flying debris breaking windows in homes; auto damage.

“You’ll have all sorts of different perils that we can only surmise,” Harden said.

He noted that the 97-98 El Niño resulted in several auto claims, including numerous totaled vehicles that were flooded out in underground parking garages.

He declined to share loss figures that Farmers incurred from previous El Niños.

“We had several thousands of losses as a result of the 97-98 event,” he said. “We certainly could expect to see a number of claim events as a result of an El Niño as predicted. We are preparing for whatever comes our way and hoping for the best for everyone involved.”

Related: