It hasn’t been healthy. In fact, the directors and officers liability insurance market for super-sized Enrons, WorldComs and the Fortune 1000 has been unhealthy for some time.

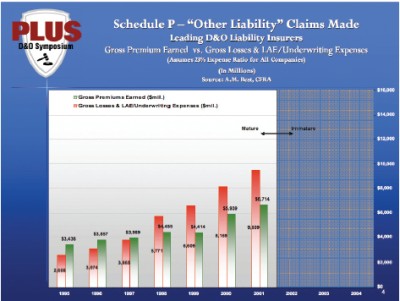

Looking at the market’s performance, Marc Siegel, director of research for the Baltimore independent research firm CFRA, notes that the period from 1998 to 2002 was extremely unprofitable. Gross losses and loss adjustment expenses exceeded gross premiums by more than $1 billion in 1998; more than $2 billion in 1999 and 2000, and nearly $3 billion in 2001. Losses from those years developed a lot worse than initially estimated–about $4 billion or 20 loss ratio points worse on average per year, according to CFRA.

As bad as Siegel’s numbers for D&O show those years were, the reality was probably even worse. His analysis (based on Schedule P- Other Liability) includes errors and omissions along with D&O results. It is generally acknowledged that E&O performed better than D&O. Remove the E&O and the picture darkens.

Also it could have been a lot worse for primary carriers had it not been for reinsurers, according to Siegel, who presented his analysis at a recent Professional Liability Underwriting Society symposium on D&O in New York City. During 1998 through 2001, ceded loss and loss expense ratios exceeded net by a whopping 44 points on average, reflecting that reinsurers paid a fat share of soft market losses.

Joseph Taranto, chief executive officer, Everest Re Group Ltd., agrees that primary carriers’ results would have been a lot worse had it not been for reinsurance. “Many of the deals struck in those days didn’t lead to people sharing and the reinsurers got the short end of the stick, so the numbers were ugly,” he said.

A D&O recovery from the years of Enron and WorldCom and other mega-claims is far from certain. D&O claims take about two and one-half years on average to mature, so while the numbers for 2002 through 2004 look better, they are still immature. Premiums grew about 35 percent in 2003 and 2004, which has helped keep combined loss ratios for those years close to 90 percent. But then premiums declined about 10 percent in 2005. Siegel also reports that 2002 has already shown additional adverse loss development through 2004 of about $800 million or 13 loss ratio points.

Siegel believes that 2003 and 2004 could still prove unprofitable judging from past trends. He is also concerned that financial restatements related to Sarbanes-Oxley could invite litigation. Through the first 10 months of 2005, there were 971 financial restatements as compared to 619 for the full year in 2004.

“While seemingly improved over the last couple of years in terms of profitability in D&O business, the recent accident years aren’t really fully seasoned and there could be some additional deterioration as the class action suits come forward,” Siegel cautioned.

Future of super-sized D&O

As Everest Re’s Taranto described them, the results in D&O have been “ugly.” So ugly that D&O professionals stay awake at night wondering if D&O for giant corporations is still worth writing. Christopher Cavallaro, president, ARC Excess & Surplus LLC, based in Garden City, N.Y., is among those who question whether money can be made in this line. “It appears almost impossible to deal with this business from an underwriting point of view,” Cavallaro commented at the PLUS symposium.

Why, he asked, are companies still writing it, especially at lower prices than last year? Why does it continue to lure capital?

There apparently are a number of answers. One veteran joked that the main reason his company is still writing D&O is because he has no marketable skills in another field.

Others cited more traditional reasons for sticking with it. “Some of the answers include the future will be better. Another answer is everyone is better than average in terms of their picking. We’ve learned the lessons from the past. Prices are down but that’s OK because losses will be down because of Sarbanes Oxley or something else,” offered Taranto.

As for why the line still attracts capital despite its lousy performance, Taranto thinks there’s one main reason: “The bottom line is that this is a business that is relatively easy to get into. If you have enough money, it’s easy to get into the reinsurance business and the insurance business.”

Another reason insurers remain in D&O could be wishful thinking. “We just don’t know yet … maybe we’re very optimistic,” offered Michael Sapnar, senior vice president, Transatlantic Reinsurance Co.

Looking ahead, some see cause for that optimism in Sarbanes-Oxley and in better management, information gathering and technology.

Taranto suggests that Sarbanes-Oxley might have a positive impact on the claims environment since so many people have to sign off on earnings reports now. But CFRA’s Siegel is skeptical. “It is cyclical. When the economy is bad, that’s when the shenanigans start. If the economy is going OK, Sarbanes-Oxley will be deemed to have been a success.”

If SOX won’t bring a recovery, perhaps better management will. “From a D&O underwriter’s perspective and running a business, I’m cautiously optimistic that we are doing things a lot better,” Tim O’Donnell, executive vice president, ACE USA, said during a separate PLUS discussion on the future of D&O. “We have a better shot at making money in the D&O business today. Risks are high, but because we better understand that it is a financial management and risk management business, then we conduct our business on the lines of compliance, and we’re going to be better off.”

John A. Rafferty, vice president, Hartford Financial Products, has faith that technology could turn things around. “We have no excuse now not to know about our portfolio. Technology allows us at any given point to know how many Fortune 500 companies we have, our book of business and profile. It takes discipline and I think the jury is still out whether or not we are going to effectively use that technology.”

“We still have to make judgments every single day,” continued O’Donnell. “As we move into soft markets, are companies going to have discipline and are people going to be willing to walk away from certain business? If we use the information we have, we shouldn’t lose as much as we have in the past.”

But Sherron M. Williams, senior vice president, XL Insurance (Bermuda) Ltd., doesn’t share O’Donnell’s optimism. “I still see rates falling; I still see a lot going on and wonder if we’re just going through another cycle,” she said.

Downsized D&O

While these veterans of traditional D&O try to figure out if they have a future, others claim they have already found the future of D&O. They found it by turning from the Fortune 1000 to the millions of mid-sized firms.

It’s called the middle market and it’s looking brighter and brighter to underwriters, agents and brokers. Whereas those in traditional D&O worry about survival, the middle marketers are worried about keeping up with the volume of new submissions and grappling with questions of efficiency and education.

“The middle market is gaining a lot of attention. It is truly a growth area in underwriting,” according to Patrick M. Kelly, attorney with Wilson Elser Moskowitz Edelman & Dicker LLP, who opened discussion on the “Middle Market Underwriting for D&O: How Sweet It Is or Isn’t” at the PLUS gathering.

JoAnne Leifert, underwriting manager with MAG Global Financial/HCC Global Financial Products, who did some research into the matter, says that while the middle market is focused on private and not-for-profit organizations, it’s a bit of a moving target. “Everyone in this industry, whether they are a carrier or an underwriter, defines middle market differently,” Leifert found.

Leifert discovered that carriers generally begin marking the middle market at businesses with $250 million in assets; only a few carriers look at anything smaller. Some start at $500 million and for others, the middle market can be up to $1 billion in assets. But above that, middle market terms don’t pertain.

The middle market can also be defined by employee count, with the lower tier being employers with 100 to 50 or fewer; the middle tier being employee count of 1,000 to 500 or fewer; and the upper tier representing those with more than 1,000 and even 2,000.

For many carriers, the middle market is also a niche of virtually any non-public company.

The point is these are not Fortune 1000, mega public firms (that tend to attract mega claims). However, what the middle market lacks in individual account size, the middle market makes up for in volume.

The private company marketplace for management liability products is roughly $2 billion in gross written premium, according to Leifert. Census figures show there are about six million businesses with fewer than 50 employees.

Daniel Auslander, vice president with CNA, assessed the not-for-profit side. He estimates that the gross premium for the middle market not-for-profit D&O segment is about $1 billion, with some 500,000 out of the potential universe of 1.5 million not-for-profit entities purchasing D&O today.

Paul Tomasi, president, E-Risk Services, a managing general agency in the Wachovia insurance group headquartered in Charlotte, N.C., sees the middle market as a bit narrower. “You have to break the numbers of firms down into potential buys. Certainly you will have some high tech companies with boards of directors who will be more likely to buy the coverage but then also that widget manufacturer in Ohio who looks at you and says, ‘why do I need D&O coverage?'”

Even Tomasi, however, sees middle market D&O becoming a $5 billion to $8 billion market in five to seven years.

This market is not immune to competitive forces at work elsewhere in D&O. “Rates are continuing to soften. It’s no surprise that the rates are softening even into first and second quarter and it doesn’t look like it is going to change anytime soon,” according to Leifert. She says an account written in 2005 for $7,000 is getting about $5,000 in 2006. “As new carriers come into the market, it only allows for more aggressive rates and more competition.”

The same is said of the non-profit segment by Auslander: “Generally, underwriting results have been favorable in this marketplace over time, and certainly that has created a marketplace that like the private that is competitive today. Rates today generally steady but certainly there are a number of players in the marketplace going after these accounts which generally are low premium accounts.”

Middle market challenges

As promising as this market appears, it is not without its challenges. Chief among these are how to operate efficiently in a high volume environment and how to educate the market on the need for the product.

According to Leifert, in terms of the volume, a middle market underwriter sees from 100 to 200 submissions a week. “In underwriting this business the last 12 or 13 years, the one thing the industry has struggled with is how to automate it,” she said. “There are struggles as far as how we grow the book and, as the volume continues to build, what the best way to write this business is and how to handle it. Is it a TPA (third party administrator) as far as claims handling goes, or is it a pure automated system that your agents and brokers can access?”

For Tomasi, the pressure is to keep up with demand. “The challenges here are basically processing. … Are we prepared? Are we ready to go to that next level? Are we ready to go onto that premium volume where it could be $8, $9 or $10 million?”

For Auslander, it’s more than processing. “The other issue dealing in a high volume environment is trying to build underwriting discipline and build an underwriting system where you are committed to the underwriting box that you developed and stick fairly closely.”

That devotion to a system is also key to the market’s early success. “It looks like the marketplace in this space is committed to this and I think overall it’s why we are generating favorable results because people are sticking to the rating model and starting to require more pricing data over time and building in a little bit more discipline in underwriting than we’ve seen in the past,” Auslander added.

According to Leifert, the industry must also face the reality that the low average premium in this segment results in commissions that are not very enticing for brokers.

Reluctant buyers

The education challenge involves agents, clients–and even underwriters.

“The challenge is how to educate our brokers to be able to sell to the non-buyer. That’s been a question in this business from day one,” said Leifert.

“Nobody wakes up in the morning and says ‘I gotta buy a D&O policy today,’ like they know they have to buy workers’ comp,” Tomasi said.

Robert O’Shea, an executive liability broker for Beecher Carlson, sees brokers’ challenge as convincing middle market buyers to pay a $5,000 premium for a coverage they aren’t sure they need. “What brokers want to bring to the table is education for clients and for underwriters. For the clients, we want to identify exposure issues. They’re going to want to know why they should be buying D&O,” O’Shea said.

“We’ve got a multitude of prospective clients out there who don’t recognize the need for buying this coverage.”

O’Shea thinks there may be overcapacity and pricing issues ahead. The $7,000 account now priced at $5,000 could represent a problem given that there are new entrants and new capacity coming in to further drive down prices. “I’m seeing a train wreck,” he warned.

But Tomasi is not so sure there’s a train wreck ahead. “The best way to avoid any train wreck, whether you’re doing public, private or non-profit, is you have to marry the underwriting data with the claims data,” Tomasi said. The price on a $7,000 account may have dropped to $5,000 but in such a young industry this may be fine. “Is that unprofitable? The answer is nobody knows when you have a whole body of underwriting data and a beginning body of claims data. We’re creating the market right now so you’re not going to know statistically … how that develops out for another five or six years.”

Auslander noted that this “certainly is a growing marketplace that has had relatively good results,” even while acknowledging that the experience in this sector, having aged only about 8 to 10 years, is fairly new.

The optimism of the middle marketers may rest on being blind to whatever claims are waiting down the track. But their optimism is also supported by the experience of their associates in the super-sized D&O market. In the words of CNA’s Auslander:

“This is an area within the management liability business that can operate more like insurance, with regard to high volume, relatively lower severity, a greater number of accounts in a portfolio and more portfolio underwriting. It’s an exciting time for this business which heretofore had been thought of a little bit secondarily, probably a little less exciting than maybe sitting down and meeting with Fortune 1000 clients. But there are only 1,000 of those. There are six million private companies out there and 1.5 million non-profits, so there are certainly great opportunities out there.

“I’m happy to be a part of the D&O underwriting segment that can sleep at night.”

Topics Carriers Agencies Profit Loss Claims Underwriting Tech Reinsurance Training Development

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Experian Launches Insurance Marketplace App on ChatGPT

Experian Launches Insurance Marketplace App on ChatGPT  Former Broker, Co-Defendant Sentenced to 20 Years in Fraudulent ACA Sign-Ups

Former Broker, Co-Defendant Sentenced to 20 Years in Fraudulent ACA Sign-Ups  World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting

World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting  Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs

Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs