This article is part of a sponsored series by Right Street.

With recovery from Hurricane Harvey just begun, and with the powerful Hurricane Irma bearing down in the days to come, policymakers are being forced to think hard about federal policies that long have encouraged development in coastal zones and other floodplains.

In that vein, new analysis from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office on the state of the National Flood Insurance Program should prove highly illustrative. The CBO’s report demonstrates that a full 85 percent of NFIP properties exposed to coastal storm surge effectively are subsidized by taxpayers – paying less than the full risk-based rate and accounting for most of the program’s expected annual shortfall.

Using data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, CBO analyzed roughly 5 million of the NFIP’s 5.1 million policies that were in effect as of Aug. 31, 2016. Summing up all of the program’s expenditures and premiums, CBO projects that, as currently structured, the program should be expected to lose $1.4 billion on an annual basis. That’s $1 billion more than FEMA’s own estimate of the NFIP’s shortfall, the basis on which it sets the program’s premiums.

According to the CBO, the NFIP rings up $5.7 billion in annual costs. The bulk of that total, $3.7 billion, is from anticipated claims, with another $1.1 billion going to private companies who write and service NFIP policies, as well as $200 million on salaries and operating expenses for NFIP and FEMA personnel. Another $700 million is spent on additional expenses, including $200 million each on mitigation-assistance programs and floodplain mapping and management. Separately, the program must spend $300 million annually to service interest on the program’s debt, which stood at $24.6 billion prior to the strike of Hurricane Harvey.

Against that $5.7 billion in costs, the program raises just $4.3 billion in annual revenues. But the top-line figure only tells part of the story. In fact, CBO’s report shows that no single piece of the NFIP’s operation is sustainable.

The program collects $3.3 billion in rate-based policyholder premiums, which isn’t enough even to cover the expected $3.7 billion in annual claims, even before you account for the fact that one-third of that total, $1.1 billion, is going to private insurers who administer the NFIP through its Write Your Own program. The program also collects $200 million from the federal policy fee, which is intended to fund administrative and floodplain-mapping costs. The mapping costs alone are equal to revenues from the policy fee.

The NFIP collects another $500 million in reserve-fund assessments, created under changes to the program in 2012 that were supposed to allow it to buy reinsurance and prepare for future catastrophic claims like the ones it experienced during Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy. However, the bulk of that money currently is used just to pay interest on the NFIP’s debt, with essentially no money left over to pay down the massive principle. The program did execute a $1 billion reinsurance program this year, and it appears Hurricane Harvey claims likely will trigger all of it, but the NFIP is not exactly well-positioned to make the even larger reinsurance cessions that it needs and that the global reinsurance markets clearly want.

Another issue concerns the roughly 1 million NFIP policies that are explicitly subsidized – primarily properties built before flood insurance rate maps were developed in the mid-1970s. CBO estimates the net cost of these policies to be about $700 million. While the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 set most of these policies on a path toward actuarial soundness, many of those changes were slowed or halted by the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014, also known as “Grimm-Waters.” To make up for the reduced revenues it would collect from the subsidized (or, in the language of the CBO report, “discounted”) policies, Grimm-Waters instituted annual surcharges of $25 on all primary residences and $250 for all other NFIP policies. But CBO estimates those surcharges raise only $400 million, leaving a $300 million hole.

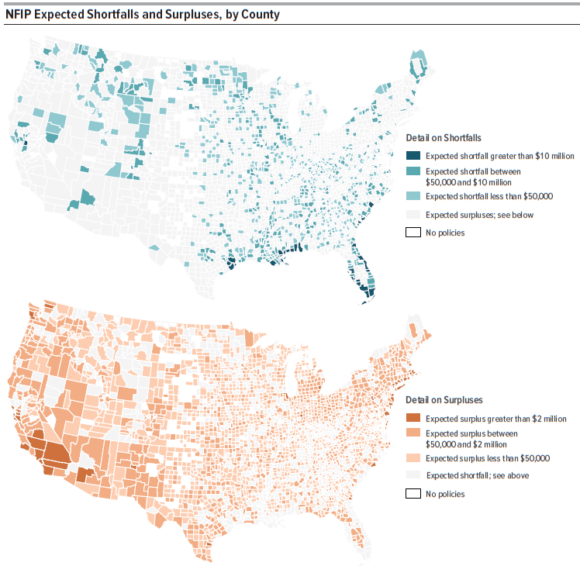

Moreover, the report makes the source of the program’s problem crystal clear. If you look solely at NFIP policies in coastal counties, the net expected shortfall is $1.5 billion a year. Inland counties actually produce a net surplus of $200 million. Breaking it down by county, CBO found 823 counties where NFIP premiums are expected to fall short of anticipated claims, for a combined shortfall of $2 billion. In particular, 33 counties—mostly coastal counties in the Southeast and along the Gulf of Mexico—each had an expected shortfall in excess of $10 million. Together, these 33 counties account for 90 percent of the total shortfall, and for 41 percent of all NFIP policies nationwide.

To understand how this is possible, it’s first necessary to grasp the outsized role that hurricanes play in the NFIP’s financials. While riverine and other floods continue to be a major issue across the country, it’s hurricanes that overwhelmingly drive the majority of NFIP claims. Over the past 35 years, 37 percent of the program’s claims came from tropical storm-driven storm surge, with hurricane-related rainfall accounting for another 16 percent.

Those statistics are even more remarkable when you consider that just 3 percent of NFIP policies are in what the program considers “Zone V” – that is, coastal areas where tidal surge adds at least three feet to the water levels reached in a 100-year flood. Not only are these coastal properties responsible for a disproportionate amount of the program’s claims, they also receive a disproportionate amount of its subsidies.

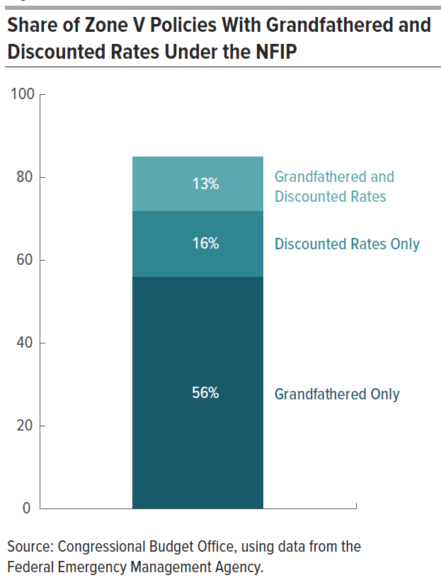

According to the CBO, 29 percent of all Zone V properties are discounted – that is, they do not pay risk-based rates because the properties were in place before flood maps were created for those communities. Separately, 69 percent of Zone V properties are “grandfathered” – that is, despite being identified by FEMA as being in Zone V, they are charged rates for Zone A (properties in 100-year floodplains that aren’t exposed to storm-surge risk) or Zone X (properties that lie outside the 100-year floodplain.) In fact, 13 percent of Zone V properties are both grandfathered AND discounted.

This should make clear the heart of the problem. Existing and longstanding federal policy asks inland residents to subsidize insurance coverage for Americans to live at the coast. This is an explicit cross-subsidy within the National Flood Insurance Program, which doesn’t even count the additional tens of billions of dollars that U.S. taxpayers have paid to bail the program out.

The subsidy also has compounding effects that tend to make it worse over time. It encourages more development in coastal regions, including in wetlands and barrier islands that otherwise would serve to absorb storm surge and dampen the destructive effects of hurricanes. Moreover, the effect of these subsidies tends to be to raise housing values in these coastal regions, leaving that much more value that needs to be insured. And these effects are before one even takes into account the impact of climate change and rising sea levels, which could serve to make the devastation that much worse.

Congress is unlikely to pass major reforms to the NFIP before its statutory authorization expires Sept. 30. In the midst of a major disaster recovery, a short-term extension is all that can be expected, putting on hold necessary decisions about the longer-term questions. But sooner or later, lawmakers will have to grapple with the words that have been with us since the Book of Matthew:

But everyone who hears these words of mine and does not put them into practice is like a foolish man who built his house on sand. The rain came down, the streams rose, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell with a great crash.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears  Insurance Issue Leaves Some Players Off World Baseball Classic Rosters

Insurance Issue Leaves Some Players Off World Baseball Classic Rosters  Florida’s Commercial Clearinghouse Bill Stirring Up Concerns for Brokers, Regulators

Florida’s Commercial Clearinghouse Bill Stirring Up Concerns for Brokers, Regulators  US Appeals Court Rejects Challenge to Trump’s Efforts to Ban DEI

US Appeals Court Rejects Challenge to Trump’s Efforts to Ban DEI