A Texas agency overseeing 13 million acres of state land is warning that toxic waste fluid from shale drilling threatens to contaminate oil wells in North America’s most prolific crude basin.

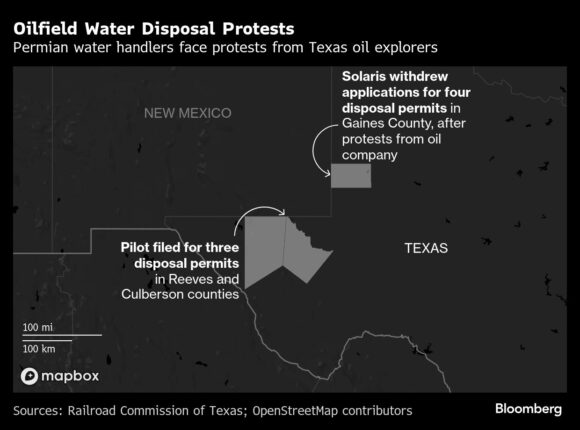

The General Land Office of Texas, which was founded in 1836 and generates billions of dollars for public schools by leasing land to oil companies, said plans by Pilot Water Solutions LLC to add three wastewater disposal wells in the Permian Basin near New Mexico would damage its nearby oil reserves.

ConocoPhillips, one of the largest producers in the basin, is also arguing against the proposal. As of March of last year, the company says it only produced 37% of the oil it expected — while generating almost double the amount of water — in the area near Pilot’s proposed disposal wells.

The pushback from the General Land Office and ConocoPhillips underscores how the wastewater problem has reached a new level of urgency. As many as five barrels of water are produced for each barrel of Permian oil, creating a major disposal dilemma.

For years, environmentalists and ranchers sounded the alarm about earthquakes and geysers caused by pumping the fluid underground. But as Permian oil output hits fresh records, the situation has grown more acute.

“Disposal of waste should not be done in a manner or location that endangers oil and gas resources,” Dawn Buckingham, commissioner of the land office, wrote in a June 2 letter to the Texas oil regulator. She said the wastewater — possibly from outside of Texas — injected into Pilot’s wells “could have a detrimental impact on oil and gas revenue constitutionally dedicated to the schoolchildren of this state.”

ConocoPhillips is the biggest producer yet to raise concerns about wastewater, but it’s far from the first.

Coterra Energy Inc. warned investors last week not to expect any oil production this year from wells that were contaminated by wastewater leaks. Before that, closely held New Mexico producer Stateline Operating Co. filed suit against Devon Energy Corp. and Aris Water Solutions Inc., alleging that toxic water leaked from the companies’ disposal wells into its production zones and rendered its reserves worthless.

Operators “are now filing more protests than they were in the past,” said Derek Cook, a Midland, Texas-based attorney at DDC Law Pllc, who is not involved in the ConocoPhillips vs Pilot case.

“They can see the real risks and problems disposal can cause to their prime investment, which is the mineral estate,” Cook said.

Read more: Shale Producers Turn Against Each Other Over Toxic Water Leaks

For its part, ConocoPhillips says water from Pilot’s proposed wells “will render a substantial amount of otherwise recoverable oil and gas reserves to be permanently left in the ground,” according to a May filing with the Railroad Commission of Texas, which regulates the oil industry.

Closely held Pilot said in a rebuttal to ConocoPhillips that its application for new wells meets or exceeds all legal requirements. It added that “in light of regional pressure concerns,” the water handler’s application includes measures that are stricter than Railroad Commission rules for disposal wells.

ConocoPhillips’ argument is “riddled with hedging language demonstrating its own lack of confidence in its hypothesis,” Pilot said in a May filing.

The protest is still pending in the hearings division of the Railroad Commission, which recently warned that wastewater from fracking is causing a “widespread” increase in underground pressure that could harm oil reserves and freshwater resources. Representatives for ConocoPhillips, the Railroad Commission and the Texas General Land Office declined to comment.

Opposition to disposal wells has long been used by other water handlers as a way to gain leverage or slow down competitors, said Patrick Patton, vice president of product at B3 Insight, an industry water consultant. About five years ago, the Railroad Commission began to limit protests to only those directly impacted, he said.

One of those protests recently prompted Aris’ Solaris Water Midstream to scrap plans for a handful of water disposal wells in the central Permian Basin. The area — east of the zone that’s at the heart of the ConocoPhillips and General Land Office complaints — has so far seen less wastewater injection than other places, but has seen its effects in the form of surface leaks.

Contango Resources LLC, a subsidiary of Crescent Energy Co., had argued in a November filing that four of Solaris’ proposed disposal wells could leak dirty water into its production zone and “create mass degradation” of its oil and gas resources nearby.

But Solaris, whose parent company Aris recently agreed to be taken over by Western Midstream Partners LP for $1.5 billion, said last week that it won’t move forward with four wells. Solaris didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment, while a spokesperson for Crescent declined to comment.

As Permian wastewater problems proliferate, drillers are clamoring for information. After Coterra discussed the issue on its first-quarter earnings call in May, the company soon learned that it was not the only producer grappling with well contamination, Chief Executive Officer Tom Jorden said at a JPMorgan conference in New York in June.

“As soon as our call finished,” he said, “our phone rang with other operators having the same problem, wanting to talk about it.”

Photo: Pumpjacks on the outskirts of town in Midland, Texas, U.S. on Monday, April 4, 2022. West Texas, the proud oil-drilling capital of America, is now also on the cusp of becoming the earthquake capital of America. Photographer: Jordan Vonderhaar/Bloomberg

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Experian Launches Insurance Marketplace App on ChatGPT

Experian Launches Insurance Marketplace App on ChatGPT  Judge Awards Applied Systems Preliminary Injunction Against Comulate

Judge Awards Applied Systems Preliminary Injunction Against Comulate  Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance

Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance  Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears