The world remains far behind global commitments to slash methane, according to a United Nations assessment that underscores the need for rapid, aggressive work to stifle emissions of the super pollutant.

Fulfilling a pledge by roughly 160 nations to cut methane emissions 30% from 2020 levels by 2030 “is technically still possible,” but only with swift action, according to the report released Monday amid UN climate talks in Belém, Brazil.

“In just four years, we have made improvements, but we must continue to drive faster, deeper methane cuts,” said Julie Dabrusin, Canada’s minister of environment and climate change.

The assessment by the UN Environment Programme and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition offers a sobering snapshot of progress since the 2021 launch of the Global Methane Pledge. Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas — with roughly 80 times the heat-trapping power of carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after it is released — and stemming it is seen as essential to keep the world’s temperature rise in check and avoid critical tipping points.

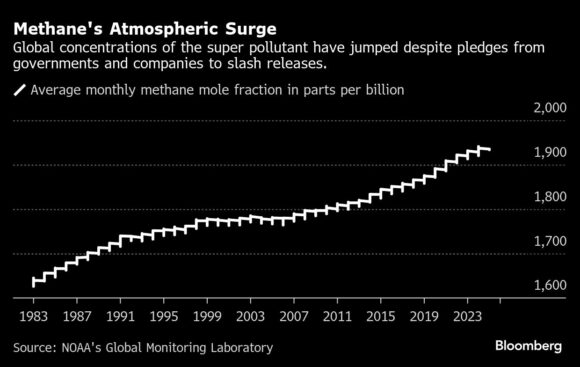

Although the growth of methane emissions has slowed since the pledge’s unveiling four years ago, they are still rising, according to Monday’s report. That’s feeding frustration — and new calls for a global methane treaty that would be modeled after the Montreal Protocol that drove down ozone-depleting hydrofluorocarbons after a 2016 amendment.

Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley has implored nations to forge an international methane treaty, with calls at September’s UN General Assembly and at a leaders summit earlier this month ahead of the Belém negotiations. Emmanuel Macron, the president of France, also has endorsed “binding objectives on methane,” and the idea has won support from some small island states on the front lines of climate change.

Yet some environmentalists focusing on methane reductions argue the long, diplomatic work of building a new legally binding treaty would steal precious time and attention from the urgent fight to arrest those emissions now.

“The methane issue is about rolling up our sleeves and getting the job done. That’s not easy, but it’s not clear to me a treaty would make it any easier,” said Mark Brownstein, a senior vice president at the Environmental Defense Fund.”Better to spend time actually working with companies and countries to get the reductions done than to spend the next several years negotiating process and essentially be right back where we are today — but having kicked real action five or 10 years around the road.”

Already, policies limiting methane emissions from pneumatic controllers, compressors and other oilfield equipment are helping drive reductions that could be replicated globally with existing technology, environmentalists argue.

In the US state of New Mexico, emissions controls have driven down methane releases equivalent to 1% of global methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, according to calculations from the Environmental Defense Fund using data from satellite observations and the International Energy Agency.

“It shows you the power of regulations,” said Fred Krupp, EDF’s’s president, noting that oil and gas development in the state has nonetheless “proceeded very rapidly.”

The energy sector alone could deliver up to an 86% reduction in methane emissions by 2030, said Jonathan Banks, a global director at the Clean Air Task Force. But though “we are seeing stronger oil and gas regulations take hold,” there remain “persistent gaps in enforcement, monitoring and finance,” he said.

Monday’s report suggests the world is at a critical juncture. According to the analysis, simply living up to existing pledges would yield significant methane reductions — but emissions would continue to rise if countries don’t enact more policies to contain them.

If nations fulfill their individual Paris Agreement emission-cutting commitments and national methane action plan pledges, emissions of the gas from human activity could fall 8% by 2030 from 2020 levels, the assessment found. That forecast comes even though three of the world’s largest methane emitters — China, India and Russia — haven’t joined the pledge.

Under a less ambitious scenario reflecting current policies, methane emissions are forecast to rise 5% by the end of the decade from 2020 levels. Even so, that projected growth is slower than forecast in previous assessments — down from a 9% increase expected in 2021.

To meet the global methane pledge’s signature goal of 30% reductions by 2030, countries would have to fully implement the maximum technically feasible options to contain emissions from the energy, agriculture and waste sectors. That includes employing water management measures in rice cultivation, using gas recovery systems at landfills and plugging abandoned oil and gas wells.

While doing so would cost an estimated $127 billion annually, the UN estimates it also would avoid some 0.2C of warming, prevent 19 million metric tons of crop losses and yield other benefits worth $330 billion each year by 2030.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Marine Insurers Cancel War Risk Cover as Iran Conflict Escalates

Marine Insurers Cancel War Risk Cover as Iran Conflict Escalates  Dubai Flights Disrupted After Drones Injure Four Near Main Airport

Dubai Flights Disrupted After Drones Injure Four Near Main Airport  Travelers Stranded by War Learn Insurance Won’t Cover Flight Cancellations

Travelers Stranded by War Learn Insurance Won’t Cover Flight Cancellations  Indiana Church Not Owed Replacement-Cost Payment for Fire Damage

Indiana Church Not Owed Replacement-Cost Payment for Fire Damage