Most of us who sit down with our beverages and snacks to watch one of the biggest events in pro sports on Sunday won’t have things like workers’ compensation and cumulative injury on our minds.

Just Brady vs. Ryan, Quinn vs. Belichick, when the New England Patriots square off against the Atlanta Falcons in Super Bowl LI.

Other than maybe a handful of hardcore claimants’ attorneys, or possibly some geeky actuaries who love their jobs, there is one man who can’t help but have these topics on his mind during the big game.

La Jolla, Calif. resident Toby Kimball may not be someone who’s synonymous with workers’ comp or cumulative injury, but perhaps he should be.

Kimball is considered by some to be the first pro athlete to file a cumulative injury workers’ comp claim in California – and possibly the nation.

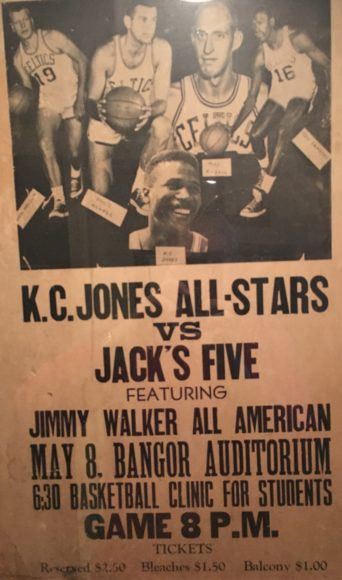

Kimball, 74, played in the National Basketball Association with some of the greats – Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Oscar Robertson, Jerry West, Wilt Chamberlin, Bill Russell, John Havlicek.

His career in the NBA lasted from 1966 to 1975 while playing for the Boston Celtics, San Diego Rockets, Milwaukee Bucks, Kansas City Kings, Philadelphia 76ers and New Orleans Jazz.

There is no definitive proof he’s the first cumulative injury case in pro sports; that’s difficult to discern. However, a San Diego Tribune article in Nov. 3, 1978 held up his just-won cumulative trauma claim as a possible “landmark decision,” after his attorney successfully argued that the years of pounding in the NBA on his knee caused it to get progressively worse.

Roger McNitt, a former chief deputy insurance commissioner for California, and someone who is intimately familiar with Kimball’s case, believes the claim opened the door for other athletes in basketball, baseball and eventually football.

“Toby started it all. He was the first one as far as I know,” McNitt said.

Nowadays cumulative injury and pro sports are common themes in sporting news outside of stories focused on the sports themselves. The term “cumulative injury” is being uttered in soccer, hockey, motorcycle racing, action sports.

In the NFL, the term “head trauma” is a headline grabber, and workers’ comp claims seem to be a more common occurrence.

The Houston Texans and quarterback T.J. Yates recently got in a tussle over a workers’ comp claim after he injured his knee in 2015. Yates, who went without a football salary for nearly a year before he signed with the Miami Dolphins in December 2016, is still contesting the Texans’ denial of his income replacement benefits through an appeal process, according to an article in the Houston Chronicle.

A few states see this trend as troublesome and are working to stop pro athletes from getting lifelong workers’ comp medical benefits.

In Illinois Senate Bill 12 was introduced to end disability benefits for pro athletes at age 35.

California already has such a law, one enacted nearly three years ago that barred most pro athletes from filing workers’ comp claims.

According to an L.A. Times article from 2014, the publicity from the high-profile battle over the bill as it made its way to becoming law prompted players from around the country to file more than 1,000 injury claims just prior to a September deadline.

A great deal of attention was garnered last year by a federal case brought by 38 former NFL players seeking to get the league to recognize chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) as a covered disease under workers’ comp.

The case was eventually withdrawn, and the players decided to file separate workers’ comp claims in individual states.

Kimball’s Knee

Kimball played basketball in a different era, when injured athletes often didn’t have much better care than a man on the street – and they didn’t earn a whole lot more.

To earn extra money, players like Kimball barnstormed in the offseason, traveling to smaller towns and putting on exhibition games. This was all on top of the beating their bodies took during the regular season.

“You’d go out and play an exhibition game and maybe make 100 bucks,” he said. “And in those days that was good money.”

The 6’8″ center was drafted in 1965 by the Boston Celtics in the 3rd round out of the University of Connecticut. However, he played his first year in Italy after a call from the head of a team in Italy looking to recruit the top college rebounder in the U.S.

Kimball was averaging 21 rebounds a game in his final year in college.

“I was a leaper,” he said.

He opted to accept the offer and play for Varese outside Milano instead of going to the Celtics because the money was good money compared to the NBA. In Italy he made more than $30,000 his first season and he was set to make $50,000 the second. During his first year in NBA he made $9,000 with the Celtics.

It made sense for him to stay another year in Italy, but when he called Red Auerbach, the coach of the Celtics at the time, to ask to play another year in Italy to “fine-tune” his game, Auerbach told him he had better come back to the team or else.

“When he said get back here or I’m going to ruin you I listened to him,” Kimball said.

He returned from Italy to the Celtics, and quietly sat on the bench throughout the season.

Then came a blowout game against the New York Knicks at the end of 1966. The coach took out the veterans and put in the rookies.

Kimball got put in, played for a time and did what he did best – boarding. Toward the end of the game he went up for a rebound off a missed shot.

“As I came down I was turning to pass the ball down the court on a fast break, so as I came down my kneecap went from the front of my body to the back of my body,” he said.

He recalls NBA great Russell holding his head up while doctors on the court worked to manipulate his kneecap back in place. Russell was holding his head because he was banging it on the hardwood court in hopes of passing out, Kimball said.

This is where his trouble began. Rather than operating on the knee, doctors put Kimball in a body cast, which covered his entire right leg up to his waist.

“It was the wrong thing to do actually as it turns out because the muscles atrophy in your leg,” he said. “When they took the cast off, my leg was like a noodle.”

After the cast was removed he was sent to Harvard University’s athletic department for rehab. Trainers there worked on the knee to try and improve flexibility, but the therapy had the opposite effect. It wore the cartilage and further damaged the ligaments, according to Kimball.

“Going in and having that done once or twice a week was extremely painful,” he said.

Kimball, who portrayed Auerbach as a shrewd decision maker, said Auerbach knew there was an expansion draft coming as more NBA teams were being created, so he decided to move on from the injured player.

Rockets

Kimball was picked up by the San Diego Rockets in 1967, the team clearly not cognizant of the extent of his injury. Team managers soon realized he had problems with his knee, but they put off any operation until the end of the season because they didn’t have enough players. And Kimball was their starting center.

At the end of that season he had his first operation to repair the cartilage and ligament damage, but it was already too late for his knee. He played in San Diego four years through chronic and worsening knee pain until the team moved to Houston in 1971.

Throughout his career he fought game after game, and season after season, to stay healthy and manage the bad knee.

Physicians on the teams he played for employed a patchwork of treatments to keep Kimball in action, including medications like Phenylbutazone, which is no longer approved for use in humans, and using a needle to remove excess fluid from the knee, as well as using an exercise bike and lifting weights.

By that time his knee had become a theme at season’s end, when team managers and doctors would tell Kimball that he wouldn’t last through another year.

To his credit, he lasted until 1974 with the New Orleans Jazz, his final season.

When he went to the Jazz he figured he’d sit on the bench, but an injury to starting center Neal Walk meant Kimball would play 40 or more minutes in each of the next three games.

“I played three games that season and at end of the third game I couldn’t even walk, my knee was like a balloon,” he said.

One day when the season had just ended, Kimball was sitting in a whirlpool to try to relieve the pain.

“They handed me the phone and I was told ‘We don’t need you anymore, you’re through,'” he said.

Instead of just packing it in, he decided to try and defend himself.

He called Larry Fleisher, an attorney and sports agent who helped found the NBA Players’ Association, to see what could be done.

Fleisher told Kimball that waiving an injured player was a violation of the collective bargaining contract.

The players’ association and NBA went through an arbitration process and Kimball eventually won a disability claim. He was awarded two-thirds of the salary he would have received for playing that year, which by then was up to $50,000.

Looking back, Kimball believes that his knee troubles weren’t the only health problem that can be attributed to the rigors of playing in the NBA during a time when players were treated less with less regard.

Teams in that era flew commercially. A team could play in New York one night, Los Angeles the next and Boston the next. It was a lot of hard playing, then waiting for a plane to take off, then a long flight, then playing vigorously again, sitting, practicing.

At age 50 he was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, in which the functions of the four heart chambers are out of sync and produce irregular heartbeats. A few years later he suffered a series of mini strokes.

“It was kind of a joke – what you see today vs. what we had to go through,” he said. “You can point to stress and strain and travel.”

As a rebounder who was often in the thick of things, so it’s no surprise he suffered a few concussions, a much talked about issue today, particularly in the NFL. But such injuries were commonly dismissed at the time, he said.

“We used to get knocked around and you were out there and not sure where you were running,” he said.

Workers’ Comp Claim

Kimball was playing tennis in 1976 at La Jolla High School with his friend McNitt, who is now an attorney at Blanchard Krasner & French. The pair were friends and neighbors, and they served on the local school board together.

McNitt noticed how hard it was for Kimball to play and then recover.

“After we played tennis he would have get into the Jacuzzi or he couldn’t walk for a week,” McNitt said.

For McNitt, a way to help his friend’s suffering immediately presented itself. In his capacity with the California Department of Insurance he spent a big portion of each work week finding a way to deal with a “cumulative injury crisis” at the time.

By the late 1960s there was a rapid growth of cumulative injury claims. The path for cumulative injuries was paved by a court ruling in the 1950s on back injuries, so by the next decade claimants’ attorneys began catching on. The problem grew worse into the 1970s.

Things got so bad that the California Assembly Finance, Insurance, and Commerce Committee called a hearing on the solvency of the State Compensation Insurance Fund in 1977. That committee also had a subcommittee looking into assuring workers’ comp payments for cumulative occupational injuries.

Cumulative injury losses for the State Fund had grown from 7.3 percent of total losses in 1969 to 21.6 percent in 1976, according to an article penned by Joseph La Dou, M.D. in the September 1978 issue of Journal of Western Medicine. The article also noted that the numbers for Industrial Indemnity, a large workers’ comp carrier, rose from 1.4 percent in 1969 to 15.7 percent in 1976.

The crisis was fixed by a 1977 bill amending Labor Code Section 5500.5. Before that bill became law, cumulative injury loss claims could be filed against nearly all prior employers. Many claims included an employer going back 20-plus years, so the cost alone of finding old records was substantial.

Under the 1977 legislation, liability claims for cumulative injuries filed after Jan. 1, 1978 were limited to employers during the immediately preceding four years. The four-year period was thereafter reduced by one year annually so that claims filed after Jan. 1, 1981 could only be filed against employers in the prior year.

“The issue was solved by a lot of hard work by all concerned, including employers, unions, worker’s compensation judges, the insurance industry – particularly the State Fund and Industrial Indemnity – the insurance department and the Legislature,” McNitt said.

With all his work on the cumulative injury crisis fresh on his mind, McNitt looked at his limping friend after the tennis match and told Kimball he should file a cumulative injury claim.

Emboldened by his disability claim victory against the against the Jazz years earlier, Kimball figured it wasn’t a bad idea, particularly if he needed more knee operations.

McNitt found Kimball an attorney, Howard Scott, a workers’ comp lawyer in San Diego, and every team he played for was a named party in the claim.

Despite the opposition, a cumulative injury award was returned that gave him a few thousand dollars, but more importantly, he received lifetime medical benefits. He used the benefits to purchase an exercise bike, knee braces over the years and an operation at Scripps Memorial Hospital to shave off some of the bone in his right knee and clear out the arthritis.

Kimball walks with a cane now, and the last time he played tennis was at age 50, when he was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation.

He doesn’t mind reflecting on his career and his knee, which he agrees was indeed caused by the accumulation of being battered on the court and ridden hard by the teams he played for.

But he has no trouble pinpointing where it all began.

“Starting with Boston they should have had me operated on,” he said. “By the time they fixed everything, the trauma to it had caused all the arthritis.”

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles

Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles  Insurance Issue Leaves Some Players Off World Baseball Classic Rosters

Insurance Issue Leaves Some Players Off World Baseball Classic Rosters  Portugal Deadly Floods Force Evacuations, Collapse Main Highway

Portugal Deadly Floods Force Evacuations, Collapse Main Highway  Fingerprints, Background Checks for Florida Insurance Execs, Directors, Stockholders?

Fingerprints, Background Checks for Florida Insurance Execs, Directors, Stockholders?