Insurance specialist LeConte Moore and professional fine art appraiser Vincent Wiener deal with high-profile performers and artists and their works so hearing talk of big dollar figures is not unusual.

Moore says he and his insurance colleagues are not surprised to hear about claims sometimes in the tens or, occasionally, even the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But an art damage claim worth multimillions? “That’s pretty rare,” said Moore.

Thus when stories about an $18 million insurance claim for a damaged Picasso resurfaced in the news recently, Moore admits it “flew around our industry like a wildfire” because “that’s a big loss.”

Insurance broker Moore is managing director of DeWitt Stern’s Entertainment and Media Division in New York. He has been with DeWitt Stern, now a division of Risk Strategies, since 2004. Previously he led Marsh and McLennan’s Entertainment Practice.

According to Moore’s profile, his clients have included popes, princesses, rock stars and presidents. In addition to major sporting events like the Super Bowl and Ryder Cup and events at Carnegie Hall, he also serves galleries and major private collectors.

Wiener is founder of New York-based Victor Wiener Associates, a fine art consultancy and appraisal company that works on valuation matters, often pertaining to insurance. Wiener and his team also advise clients buying or selling works of art. His resume includes some of the “highest-stakes art cases in recent history” including works by Picasso, Andy Warhol and Louise Nevelson. In 2014, he was retained for the valuation of the Detroit Institute of Arts in connection with the 2014 city of Detroit bankruptcy trial. He and his team of experts valued the giant collection that included works by Caravaggio, Monet, Picasso, Rembrandt, van Gogh, and Whistler at $8.1 billion.

Neither Moore nor Wiener has been involved in this $18 million damaged Picasso case; however, with their expertise and experience in similar situations they offered to share their takes on what has transpired in the high-profile claim case.

Déjà Vu

The $18 million in damage to the Picasso actually happened several years ago; the story spilled into the news again recently because of a subrogation filing by the insurer that is trying to get reimbursed from the party it says was responsible for the damage.

The case is partly intriguing because, as Yogi Berra might say, it is like déjà vu all over again.

In 2006, casino owner Stephen Wynn accidentally poked a hole with his elbow in Le Rêve, a 1932 painting by Pablo Picasso of his young mistress, a painting Wynn and his wife owned.

The mishap occurred while Wynn was in the process of selling the painting for $139 million.

Wynn had the hole fixed and the artwork restored for $90,000. Wynn also sued Lloyd’s of London, the insurer of his art, for a sizable $54 million in lost value. He eventually settled that claim for an undisclosed amount.

Wiener can’t talk specifics but he was involved in the appraisal ofLe Rêve to determine the diminution in value to the painting due to the puncture as well as the market value of the painting prior to the accident.

He is also familiar with the intricate $90,000 restoration work done on Le Rêve.

“I think it’s very well known thatLe Rêve was restored by a brilliant conservator named Terrence Mahon, really brilliant. I’ve seen his work over the years. I’ve worked with him. He’s great,” Wiener said. Mahon actually used acupuncture needles. “He was sort of a pioneer in this, now quite a few people use it.”

Sales Postponed

Wynn ended up not selling the elbowed and restored Le Rêve at that time; instead he held onto it.

Then in 2013, Wynn soldLe Rêve for $155 million to Steven Cohen, who owns the hedge fund SAC Capital. That was $16 million more than Wynn had been offered seven years earlier before it was damaged.

So between whatever his insurance recovery plus final sale brought him, Wynn managed to create plenty of elbow room to celebrate, despite the puncture.

Five Years Later

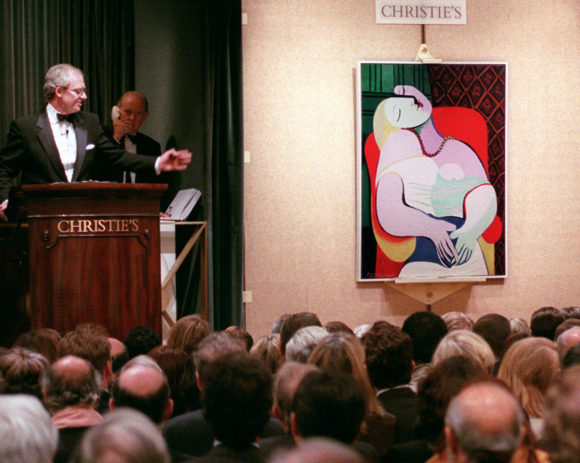

Here’s the déjà vu part. Then in 2018, Wynn ended up having a second Picasso with a hole poked in it. This time Wynn didn’t do the damage himself and the subject was a different Picasso, Le Marin. This accident happened in a gallery at Christie’s auction house right before this $100 million painting of a sailor was to be placed on display for auction. The insurer says a contractor hired by Christie’s is to blame.

This time, Christie’s paid Wynn’s art company, Sierra Fine Art, $487,625 for the cost of restoration and also $18,250,000 for the lost value of the artwork due to the damage, plus attorneys’ fees, for a total of $18,750,000.

Christie’s insurer, Steadfast Insurance, then reimbursed Christie’s for the payments the auctioneer made to Wynn’s company.

Framing the Painter

Now, Steadfast Insurance, a unit of Zurich Insurance, has gone to court seeking to be reimbursed by the persons it says were responsible for the hole in the acclaimed Le Marin. It so happens those people are painters of another kind.

Steadfast is suing a family-owned Manhattan painting and wallpapering firm, T.F. Nugent, which had been hired to paint some of Christie’s galleries, and whose employee, the insurer alleges, is responsible for the “severe damage” to the art. Steadfast wants to recover $18,750,000 plus its own lawyer’s fees from T.F. Nugent.

Steadfast claims the painting firm was “negligent and careless” in how it went about its work.

The insurer says that on May 11, 2018, the T.F. Nugent employee, knowing that paint roller extension rods were not allowed in Christie’s galleries, left one against a wall in an entranceway to the gallery only to have it fall and strike the painting. The worker then walked away.

Moore explains that this would not necessarily be an unusual circumstance. “It’s a very normal occurrence to lay paintings against the wall as you’re plotting out your show as to where it’s going to be, and how things are going to look. You want certain paintings next to different paintings and things like that,” he said.

Risk of Mishap

Wiener agrees. While a Picasso claim may be unusual, the circumstances surrounding the mishap in the auction house that led to the damage to Le Marin were not. Many art insurance claims occur when the art is in transit as it was in this case. He estimates that 90% of the damage against art is just accidental.

“When things are shown in exhibitions, there’s always a risk factor in doing one,” Wiener said.

“Every time you transport art, every time it goes to a different environment, there’s a danger. Keeps me in business. I’m very busy.”

Overall, he said auction houses have a lot of activity with regularly changing shows. In some ways it is surprising there isn’t more damage. “I think it’s actually a credit to the expertise of the people who do it that more damage doesn’t occur.”

4.5″ x 1.5″ Tear

According to the insurer’s account of what happened, the employee “did not ensure the paint roller extension rod was secure and the paint roller extension rod rolled fell the wall and fell into the Le Marin. The tip of the rod penetrated the canvas of the Le Marin in the lower left quadrant.”

The roller damaged an area approximately seven inches long and two inches wide. Within the damaged area, there was a tear measuring approximately 4.5 inches by 1.5 inches, according to Steadfast’s complaint.

Why was the Le Marin where it was when it was damaged? It had been placed on foam pads on the floor and against the wall, across the room from where it was going to be hung for auction later that same day, according to Steadfast. The complaint does not say who placed it there.

Art of Appraisal

According to court documents, two independent art experts determined the market value of the Picasso to be no less than $100 million, a value that is “reasonable and consistent with the market values of Picasso paintings of similar reputation and quality sold at auction.”

Given the extent of the damage and the “accompanying reputational damage,” the loss in value of the Le Marin was determined to be no less than 20% of its market value, or $20,000,000.

Given the extent of the damage and the “accompanying reputational damage,” the loss in value of the Le Marin was determined to be no less than 20% of its market value, or $20,000,000.

“Art insurance is tough because establishing value in art is hard, especially because there’s no right or wrong,” said Moore.

That’s why art collectors and insurance companies turn to experts like Wiener to assess the value.

As noted, Wiener did not appraise Le Marin but did work on Picasso’s Le Rêve in 2011.

According to Wiener, in appraisal situations like Le Marin, there are typically several appraisers involved because of competing monetary interests — such as owners, insurers, perhaps prospective buyers. The insurer of the clients, or their lawyers, will typically canvas a number of candidates to be the appraiser for this loss before deciding on one.

“It’s a very tricky thing and it’s very, I wouldn’t say arbitrary, but everyone’s going to have a different point of view. Generally the point of views will coincide, but there are disputes amongst appraisers on what the loss in value should be,” he added.

To arrive at a market figure, an appraiser gathers knowledge about the art, its authenticity and its condition and researches current and past comparable sales of similar works, auction records, and various prices guides.

While art is unregulated—anyone can create and sell art for whatever price thy want — a qualified, professional art appraiser adheres to the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice that instruct appraisers on coming up with “objective and independent” judgements.

Lost and Found Value

“Opinions vary and we come up with different opinions,” notes Wiener. “I never question the honesty of another person’s opinion. Whether I think it’s a smart opinion or not is another story. But the honesty of having stated it, I would never question. I’m assuming that no one is corrupt and everyone believes what they put on paper.”

When appraisers can’t agree on a figure, they meet to attempt to resolve their differences or a third party may be called upon to arbitrate.

Determining the lost value due to damage reflects the state of the market at the time. It’s not always clear that the value is lost forever.

“It depends on the artwork,” Wiener said. “It’s very, very hard to generalize and it depends upon the art. Now, in the case of Steve Wynn’s Picasso, which of course, he made a killing out of it from insurance.”

Again, he stressed, it depends on the art. “You can’t say, ‘Oh, in the long run, it doesn’t matter.'”

Although regarding Le Reve, that seems to be the case.

“My benchmark is if you were negotiating to buy that painting and you were a collector, how would you negotiate? Would you say, ‘I love this painting, but I won’t take it like this, give it to me with a huge discount or I’ll get another one like it”, Wiener posited. “I’ll get another one like it?'”

Of course, in the case of Le Reve, there is no other one like it. So if there are no other ones like it, the lost value didn’t make that much of a difference in the long run.

“Steve Cohen eventually paid much more,” he noted.

Process of Paying

In the Le Marin case, Christie’s entered into settlement negotiations and invited defendant T.F. Nugent and its insurer to participate in the settlement discussions but, according to the insurer, they declined to do so.

Christie’s negotiated a settlement with Wynn’s company, Sierra Fine Art, for $18,250,000.

Christie’s paid Sierra the $18,250,000 settlement. Christie’s also incurred attorney’s fees and costs of no less than $100,000. In sum, Christie’s paid $18,737,625 to settle with Wynn.

Steadfast then reimbursed Christie’s for the payments made to Wynn and the painting’s restorer.

In January 2019, Steadfast demanded payment from the defendants for $18,737,625, plus attorney’s fees, interest and costs, for their alleged negligence.

“These underwriters are out $18 million and they’re looking, like any insurance company, looking to subrogate, looking to get some of their money back. So, they’re going to look for any guilty party,” commented Moore.

“This is really the way insurance works. Insurance companies pay a claim. They go after others to try to get their money back. Had this been a $300,000 loss and they’re going after the painting company, it wouldn’t have gotten any press.”

Premium Advice

Going forward, Moore suggests that underwriters considering whether to insure Christie’s are going to look at what happened. They will look at the protocols, safety measures and security, and at the value of the art that is in that building. They’ll look at the losses over the past five years. They will put all that into their calculations to arrive at a premium.

“Now in this case, with this size loss, that just blew out years of premium because it’s a big, big loss. But that’s the business that underwriters are in. They’re taking, and I call it intelligent bets, based on the best knowledge they can get from risks. Sometimes you can have the best risk in the world. I’ve had clients for years and years and years,10 years, and never had anything go wrong and then, boom, a $3 million painting gets damaged,” he said.

That’s the art insurance business.

Since the story made the news, Moore has been hearing from auction houses and art galleries asking if they should require their vendors to bulk up on insurance to cover losses like this.

“What I have told people is, you have to make intelligent decisions about the quality of people you bring in. You should require them to have some insurance, and do the best you can, but you can’t require them to have amounts that would cover the artwork if they’re working around artwork,” he said.

According to Moore, art clients can’t make every vendor carry $10 million or $15 million of coverage. “A carpenter coming in to put up some bookshelves, a five person operation, isn’t going to have that kind of insurance,” he said.

As for the painting company, photographer, film company or anybody going into a museum or auction house or gallery to work, he would advise them to “contractually limit that they can’t be liable for all the amount of art in the place.”

It’s not known how much insurance or money, if any, the painting company had or has but Moore figures the insurer will likely take whatever it can get if it can prove the painting company was at all negligent.

Steadfast maintains that the Nugent family and T.F. Nugent are alter egos of each other and that the family “caused the company” to be “underinsured and undercapitalized” during the time periods surrounding the incident. The complaint seeks to impose “personal liability for misuse of the corporate form” and hold the family members liable for the damages.

Meanwhile, T.F. Nugent says it closed its doors at the end of 2019. However, according to an amended complaint by Steadfast last week, the same people behind T.F. Nugent are now operating under a new business name, NewGen Painting. The insurer claims that NewGen was “created to defraud creditors of T.F. Nugent.”

T.F. Nugent has not responded to requests for comment.

The case is Steadfast Insurance Co. v. T.F. Nugent Inc., 1:20-cv-03959, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York (Manhattan).

Topics Carriers New York Contractors

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Florida House Gives Final Approval to Much-Debated Citizens Clearinghouse Bill

Florida House Gives Final Approval to Much-Debated Citizens Clearinghouse Bill  Georgia Teacher Killed When Toilet Paper Prank by Students Goes Wrong

Georgia Teacher Killed When Toilet Paper Prank by Students Goes Wrong  Insurify’s Founders Discuss Evolution of Insurance Shopping With AI

Insurify’s Founders Discuss Evolution of Insurance Shopping With AI  Dubai Flights Disrupted After Drones Injure Four Near Main Airport

Dubai Flights Disrupted After Drones Injure Four Near Main Airport