As the Trump administration stalls federal funding for projects intended to make states more resilient to climate change and private insurers decline to cover properties in high-risk zones, North Carolina just proved there’s another way to fund disaster preparedness: a $600 million catastrophe bond that rewards homeowners and their insurer for installing “super roofs.”

Along North Carolina’s beaches, wind damage from hurricanes is such a threat that many private insurers have stopped offering coverage. Hundreds of thousands of homeowners have been forced to buy coverage fromthe North Carolina Insurance Underwriting Association (NCIUA), the state-created insurer of last resort for coastal properties.

Like other insurers, NCIUA has to buy its own risk mitigation so it can pay customers if a major event causes more damage than it has saved from collecting and investing premiums. One option is reinsurance and another is a catastrophe bond, which pays out a specific amount if damage reaches a particularly severe level. Cat bonds have become popular with institutional investors like hedge funds and endowments in recent years because they trigger rarely and otherwise deliver high returns.

For years, academics and brokers have discussed whether cat bonds could do more than just clean up after disasters—whether they could incentivize mitigation work that would lessen damages in the first place. Earlier this year, NCIUA decided to test it: They offered investors a cat bond with two features linked to reducing wind damage risks to homes in its portfolio.

First, if no major losses occur each year, $2 million returns to NCIUA—earmarked exclusively to incentivize homeowners to install super roofs that are especially wind-resistant. Second, as more people add these roofs, the annual pricing on the bond resets to reflect the changing exposure.

It’s modest financially but revolutionary conceptually, said Shalini Vajjhala, founder and executive director of PRE Collective, a San Diego-based nonprofit that works with communities and government agencies to clear barriers to building climate resilient infrastructure.

“The North Carolina program is game-changing,” she said. “It’s a precedent-setting way of linking how you manage your financial risks with how you manage physical risks.”

Its origins go back to 2009, when the North Carolina legislature passed a law encouraging NCIUA to look at mitigation strategy. The state was worried because the number of homes insured by NCIUA was creeping up as private insurers pulled back after damaging storms. It’s similar though less dramatic than what’s happened in Florida and California in recent years as state-sponsored insurers of last resort found themselves covering more and more properties.

NCIUA officials researched options to reduce liability, landing on a seemingly simple one: roof fortification. The technique uses things like ring-shank nails, designed for gripping, and extra sealing for the roof’s underlayer and edges.

There was one big roadblock. Super roofs prevented damage, but since they exceed building code requirements and cost roughly $3,400 more than a standard roof, few homeowners installed them.

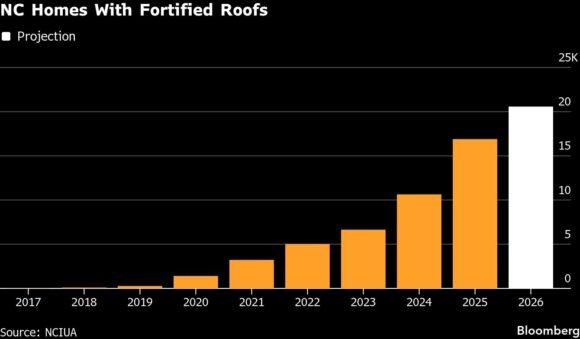

So in 2017, NCIUA began offering free super-roof replacements to homeowners who needed a new roof after a storm. They met resistance at first, said Gina Hardy, chief executive officer of the association. “With the free grants, people thought we were running some kind of scam.”

So the association engaged in consumer and contractor education. They also expanded incentives. In 2019, NCIUA offered $6,000 grants for super roofs during routine re-roofing, even though the upgrade cost just a fraction of that. They later increased it to $10,000. Homeowners essentially use the rest to defray regular roofing costs.

It was those new grants that turned Marie Raynor, 59, from a skeptic to a buyer. She’s lived in coastal North Carolina her entire life, and in 2024 her home in Wilmington, just a few miles from the beach, had a leaking roof. She received a mailing advertising the roof program, but worried it was an empty sales pitch; a call to the insurance office verified the program’s veracity.

Eight weeks after she applied, she had a new roof. And now she is “thrilled.” It was one of the most painless renovations of her life, she says, and she is convinced that the new construction is venting wind and even heat in the summer.

“I feel like it is also a rebate for all the years I paid insurance and didn’t use it,” she said.

About two years ago, the program began really catching on. Today, more than 20,574 homes have these roofs or are in the process of adding them and more than 6,000 were added just this year. And the financial benefits are already accruing. After every storm, NCIUA checks the results. They’ve found that fortified homes had 60% fewer claims than code-compliant homes during regular storms, and 20% to 30% fewer claims with lower severity during named storms.

NCIUA says its financial analysis is that it will recoup $72 million over 10 years on the investment in roofs, some from avoided losses after storms but even more from having to purchase less reinsurance because their portfolio is less risky.

With demand for roofs finally surging, Hardy wanted to make sure she had adequate capital for all the willing participants. She began looking beyond her own surplus to fund grants. Every year the association pays for a combination of reinsurance and cat bonds to cover portfolio risk. She had read about cat bonds with resilience features in academic literature and now wanted to make one a reality.

“For a long time, people have been asking, ‘Could we monetize the savings from mitigation efforts to pay for the mitigation efforts?’ But it’s incredibly complex,” said Cory Anger, managing director of insurance-linked securities at Guy Carpenter, the broker for the bond. North Carolina, however, has a five-year track record showing its program worked, which was very enticing to investors.

When the Cape Lookout Re bond was sold to investors in February, it not only secured an interest rate at the low end of expectations, according to Artemis, the industry trade magazine, it attracted far more interest than expected. Offered at $350 million, it instead drew $600 million in investor interest. “It was a really successful offering,” Anger said.

The timing couldn’t be more critical. Since taking office, President Donald Trump has held back billions in Building Resilient Communities and Infrastructure grants awarded by the Biden administration.

Many working to make homes and cities more resilient to storms and wildfires worsened by climate change are hopeful the association’s success will be a model. “North Carolina did the really heavy lifting, and when it’s done, it opens up this whole universe of opportunities where you can basically create a plug-and-socket between programs that reduce risk and insurers who benefit,” said Vajjhala.

There are reasons to believe replicating this model for other climate threats may be challenging. A direct relationship between roofs and reduced wind damage has been established. Individual efforts by homeowners to reduce fire risk, for example, aren’t as perfectly correlated because community factors like the state of nearby forests and forest breaks are also in play.

Still, Dave Jones, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley and former California Insurance Commissioner who led a team that designed and placed the first wildfire insurance policy priced to account for local forest management—including controlled burns to reduce the chance of huge blazes—argues that such bonds should interest all 35 state-backed insurance plans of last resort.

“It’s going to vary based on the circumstances,” he said. “But I think it’s worth looking at.”

Photo: A damaged roof after Hurricane Florence in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 2018. (Alex Wroblewski/Bloomberg)

Related: NC Expands Fortified Roof Program With Another $20 Million

Topics Catastrophe Carriers Homeowners

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

US Offers $20 Billion Reinsurance Plan to Spur Gulf Oil Flow

US Offers $20 Billion Reinsurance Plan to Spur Gulf Oil Flow  Greek Oil Tanker Exits Hormuz Shipping Strait With Signal Off

Greek Oil Tanker Exits Hormuz Shipping Strait With Signal Off  Kyle Busch and Wife Settle Lawsuit With Pacific Life and Insurance Agent

Kyle Busch and Wife Settle Lawsuit With Pacific Life and Insurance Agent  Travelers Stranded by War Learn Insurance Won’t Cover Flight Cancellations

Travelers Stranded by War Learn Insurance Won’t Cover Flight Cancellations