Everyone needs insurance. My entrance into the insurance world taught me that. The first place I worked in insurance specialized in providing insurance to fire departments and ambulance companies.

Municipalities and their fire departments have similar exposures as other entities do. They own property, which needs to be replaced when it becomes damaged (and fire departments know how to damage property). What’s the one thing that the fire department might forget about when responding to a fire call at your house? Right. The cook might forget to shut off the stove, and when they are done fighting your kitchen fire, they get to fight their own kitchen fire.

Not that I’ve seen that claim.

Their members (volunteer fire fighters) and employees may own property that comes to the fire station with them. That property might get damaged in the course of their work for the fire department. Cell phones don’t always fare well when the fire fighters are using the department zero turn mower to cut the grass (and their cell phone).

Not that I’ve seen that claim.

They drive vehicles that cost more than most cars you would probably have in your driveway. Sometimes, emergency vehicles have to travel faster than the speed limit in order to get to the scene of an emergency. Every once in a while, driving faster than the speed limit causes events that end in damage to a very large and expensive truck.

It had never occurred to me that a fire department, doing its duty to protect life and property, might face claims of negligence. But it happens more often than we think. I would have thought that a fire department, since it acts in good faith to help the people of an area as a governmental entity, would have some kind of immunity to lawsuits. Turns out that they don’t always enjoy that kind of immunity.

Yet, fire departments, municipalities, and other governmental agencies could do something in good faith and still be negligent in some way. In order to show negligence, the following must be determined.

- Was there a duty owed?

- Was there a breach of that duty?

- Was that breach the proximate cause of injury?

- Were there damages because of the injury?

For example, a fire department is called out to respond to a brush fire. One of the volunteer firefighters responded in their personal vehicle. Once on scene, they were given the task of traffic control because the fire department needed to access the scene and smoke from the fire was blowing across the road, making it difficult for drivers to see.

As it happened in this story, the wind shifted enough that visibility became low away from the original traffic control point and a driver came upon the stopped traffic and didn’t notice that it had been stopped, causing an accident.

The question then becomes who is negligent in this situation? Arguments could be made for the driver, who owed a duty to be a careful and observant driver, who may have breached their duty to drive carefully, because they caused an accident with property damage to vehicles. Of course, there could be an argument made that the fire department was negligent because the fire fighter had a duty to set up a safe and easily seen traffic control point. Since a driver didn’t see that traffic was stopped, the failure to mark the traffic control point caused the accident and the property damage related to it.

But what about immunities? Aren’t governmental entities provided with some immunity to tort liability? That depends.

Some governmental entities enjoy a degree of immunity from tort liability, based on the tort, the damages sought, and the jurisdiction. Individual state laws and court rulings make it difficult to pin down whether an aspect of a governmental entity’s functions is immune to tort liability or not. The presence of insurance, rather than making it easier, can make it more complicated.

Some states have decided that they have a need to control the tort liability of their governmental entities, and while they may not enjoy full immunity, some states have enacted caps on recoverable damages and immunities against certain kinds of damages.

Let’s look at a few states for examples and how insurance plays into it.

Florida caps damages for tort claims at $200,000 per person and $300,000 per claim. Any claims above that amount must be reported to the state legislature, and the legislature must decide whether or not to pay that excess amount.

Complicated and time consuming, but not too complicated yet. If the governmental entity has liability insurance in place that exceeds the $200,000 per person or $300,000 per claim cap, the insurance can settle or pay that claim up to the limit of the insurance policy without legislative consideration. This all means that the cap is the cap unless the insurance policy or the legislature say so.

Delaware caps damages at $300,000, unless the entity elects to buy insurance that exceeds that limit. That makes the limit of recovery the limit of insurance. This is similar to Florida, except much easier to understand without adding the legislature’s responsibility to muddy the waters.

In Illinois, there are no caps on damages, but there are significant governmental functions that are immune to tort liability and others that are exempted from immunity. They have also added to their statutes the provision that the presence of insurance does not alter any immunities that they might enjoy.

In the end, the question still remains: Can a governmental entity be held liable for tort claims? And the answer remains the same. It all depends on the claim.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

After Florida Charged People With Selling Insurance Licenses, 12 More Arrested

After Florida Charged People With Selling Insurance Licenses, 12 More Arrested  Chubb to Serve as Lead US Insurer for Gulf Shipping Amid Iran War

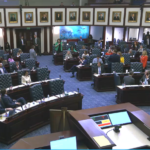

Chubb to Serve as Lead US Insurer for Gulf Shipping Amid Iran War  Florida House Gives Final Approval to Much-Debated Citizens Clearinghouse Bill

Florida House Gives Final Approval to Much-Debated Citizens Clearinghouse Bill  Marine Insurers Cancel War Risk Cover as Iran Conflict Escalates

Marine Insurers Cancel War Risk Cover as Iran Conflict Escalates