When churning flood waters swept away a group of tourists in Pakistan’s Swat Valley in June, the whole country felt a sense of déjà vu.

Just three years ago, extensive floods had swallowed entire hotels and families vacationing in the “Switzerland of Pakistan” and caused more than 1,700 deaths and billions in damage in other districts. Today, extreme rainfall has once again inundated swathes of the country, underscoring its status as among the world’s most climate-vulnerable.

The relentless tragedies highlight how woeful Pakistan’s disaster preparedness remains, as lofty climate funding pledges from advanced, higher-emitting countries and multilateral donor agencies fail to materialize. The shortfall is emblematic of the grim irony facing small, less-developed economies that contribute minimally to climate change but bear the brunt of its impacts.

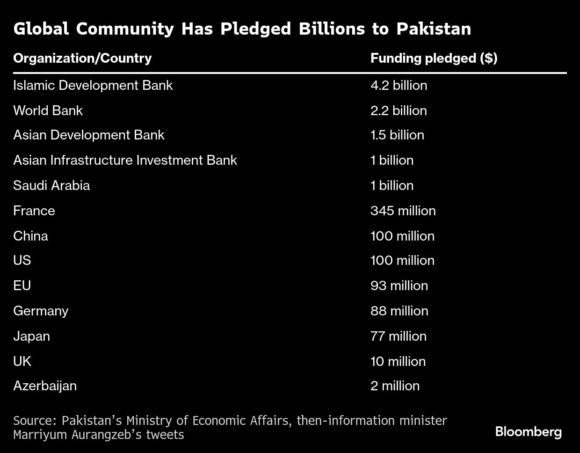

Less than half of the roughly $11 billion pledged by the European Union, China, Asian Development Bank and others in the wake of the 2022 floods has reached Pakistan, said the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, citing government data. Projects have been or are being identified for about three quarters of the total pledged amount, according to the Ministry of Economic Affairs.

Meanwhile, the country—which is also confronting multiple economic and political crises—has cited World Bank calculations that it needs $348 billion in investment through 2030, including $16 billion just to recover from the last disaster.

“The number one problem for Pakistan’s ability to do what it needs to do is the lack of financing,” said Mohamed Yahya, the United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for the country.

What has been disbursed of that pledge — about $4.5 billion as of June — has gone to rebuilding housing, transportation, drainage, and toward flood risk management.

The ADB has provided $528 million for initiatives including a reconstruction project in Sindh province and to rebuild climate-resilient infrastructure, a spokesperson said in an email. And the World Bank has channeled about $1 billion in new financing to reconstruction and adaptation projects in the Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces, a spokesperson said in an email. The organization has also approved financing of $600 million on top of its original pledge.

But officials say it’s far from enough.

Globally, the UN estimates the funding gap for climate adaptation is at least $187 billion a year. That’s in part because developed countries have been slow or reluctant to follow through on funding commitments announced on the international stage. Many EU countries, facing fiscal pressure at home, are trying to push economic giants like China to share the climate aid burden.

A pullback from the fight against climate change in some Western countries — including the US’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement — is further slashing aid.

Financing is also slow to flow because it’s often offered in the form of loans or is redirected from other projects, making it less palatable to emerging markets as it increases their debt burden and routes capital back into developed markets.

And finally, developing countries often lack the ability to use climate financing effectively. Pakistan’s Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb said in August that his country had failed to develop enough investable flood-related projects to benefit from the pledges that came after the 2022 floods, according to local news reports.

The South Asian nation has also been buffeted by corruption, political upheavals, and poor resource management, leaving it with little fiscal room to bear the costs of climate adaptation.

The government has “to ensure that they do their homework in terms of needs of the communities across Pakistan and then develop plans accordingly,” said Imran Khalid, an environmental scientist based in Islamabad. Urban planning needs to be improved to prepare for excessive rainfall, and systems put in place to manage complex financing and large-scale projects, he added.

Pakistan’s national adaptation plan says funds should be channeled toward infrastructure for drought-flood cycles in agricultural areas, developing early warning systems, and constructing wetlands and open spaces to capture runoff. Last month, Climate Change Minister Musadik Malik said in parliament the government is developing a strategy to disburse and track climate-related flows.

The country is making some progress on improving disaster preparedness. In July, it launched a remote sensing satellite for round-the-clock disaster assessment in collaboration with China. The government is also working with the UN to train officials and install early warning systems in the vulnerable valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

It can’t come too soon for Pakistan, a country with more than 7,200 glaciers — the highest tally outside polar regions — whose melt combines with annual monsoons to make floods its most frequently occurring natural disaster. Rainfall at one point this season was 82% higher than a year ago, the national weather agency said. Nearly 900 people have died, thousands have been forced to evacuate, and acres of crops destroyed.

“If devastating events continue to happen along the way, at various points, they can add to the economic burden,” said Zeeshan Salahuddin, a partner at Tabadlad, a think tank based in Islamabad. “And this is why Pakistan really needs to focus more on finding innovative finance solutions.”

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Judge Tosses Buffalo Wild Wings Lawsuit That Has ‘No Meat on Its Bones’

Judge Tosses Buffalo Wild Wings Lawsuit That Has ‘No Meat on Its Bones’  Lemonade Books Q4 Net Loss of $21.7M as Customer Count Grows

Lemonade Books Q4 Net Loss of $21.7M as Customer Count Grows  Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles

Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles  Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance

Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance