The new year may mark the last time Texas farmer LG Raun plants a rice crop.

“I guess I’m going to be the one that’s going to screw up the tradition of growing Raun family rice,” said the third-generation producer, whose family has been in the business for more than a century. “I’m not going to keep doing it and lose everything that I have, so if there’s not a big turnaround, ’26 is my last year farming.”

Raun epitomizes why rice growers were the biggest beneficiaries when the US Department of Agriculture unveiled details of its $12 billion farmer aid package last week. Payments for rice are set at $132.89 per acre, more than quadruple the amount allocated for soybeans and triple the rate for corn. The only other crop with a payout over $100 an acre is cotton.

“If you’re a rice farmer, if you’re a cotton farmer, you definitely, definitely, definitely need this tariff bridge. You need it in the worst way,” Iowa corn and soybean farmer Brent Judisch said last month.

While much of the focus has been on growers of row crops such as soybeans amid the Trump administration’s trade spat with China, rice farmers arguably have been suffering even more outside the spotlight — and for reasons that have little to do with the president’s tariffs.

Rice has been hit along with other crops by low commodity prices, high input costs and an overabundance of world supplies. But US rice has the highest costs of all major field crops for seed, fertilizer and hired labor, according to the USDA. That makes it expensive to produce even as consumer preferences for imported varieties such as jasmine from Thailand and basmati from India limit domestic demand.

US farmers also argue that subsidized exports from competitors are fueling a global supply glut. World rice supplies are expected to rise for the third straight year to a record 730.7 million tons, according to the USDA.

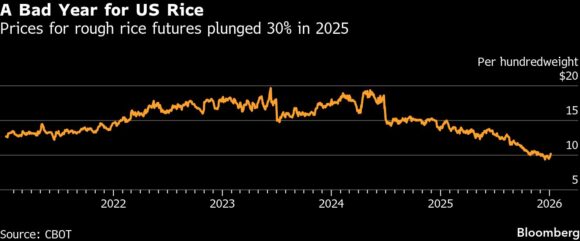

All of that helped send futures for rough rice plunging 30% last year, the biggest drop since 2001 and one of the worst performances among agricultural commodities. With American growers forecast to lose an average $437 per acre, according to a Bloomberg analysis of USDA data, the crop has shifted from a staple of Southern agriculture to a financial liability.

“It’s been one of the longest and strongest bear markets we’ve ever had,” said Milo Hamilton, chief executive officer of rice advisory service First Grain. He estimates acreage this spring in the US could fall by 30%, mirroring the decline in futures. “The market is telling them to plant anything except rice.”

Arkansas farmer Jennifer James said that while she was getting roughly $15.50 a hundredweight for her rice in the 2024 season, if she tried to sell it now for the 2026 season, she’d get roughly $5 a hundredweight less. “There’s just no margin,” she said.

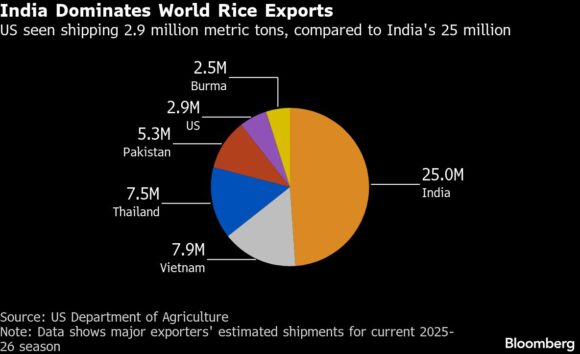

While sky-high input costs are wiping out margins for growers, the export market is having an equally devastating impact, as competition from other countries is taking away market share both at home and abroad. US-grown rice accounts for less than 2% of worldwide production, yet the nation has recently ranked as the sixth-largest exporter — shipping almost half of its annual harvest abroad.

“We’ve seen a lot of foreign rice start to infiltrate our core markets in Latin America and in Mexico,” said Michael Deliberto, an associate professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness at Louisiana State University. That includes countries in Asia where government policies help lower the price of the commodity.

American growers say India’s support for its rice producers amounts to an unfair advantage. More foreign supplies are also flowing into the US, with imports through September up 11% from a year earlier.

Aromatic varieties from Asia make up more than 60% of US rice imports, according to the USDA. Such fragrant varieties are preferred by some consumers in the US for the taste and cooking attributes, Deliberto said.

President Donald Trump has signaled he could impose tariffs on rice from India, the world’s largest exporter that is expected to sell about 25 million tons this season. He has also pointed to Japan not importing US rice even when supplies were tight.

Meryl Kennedy Farr, chief executive officer of Kennedy Rice Mill in Louisiana who sat next to Trump as he announced the farmer bailout plan last month, emphasized to the president that the situation is “not just a crisis” but “anti-competitive.”

“We see countries overproducing,” Farr said in an interview with Bloomberg. “When their stocks are full, then they flood the market and really depress prices globally.”

Charles Williams, another rice farmer who met with Trump and USDA officials at the White House, echoes those concern. “We’re not on a level playing field,” he said. “I think we’ve got some de facto dumping of rice on the world market.”

He’s predicting that in 2026 producers in Arkansas, the top rice-growing state, may plant less than 1 million acres for the first time in more than 40 years. For his part, he’s considering switching to more soybeans and less long-grain white rice.

Others are also contemplating their options. James, the farmer in Arkansas, is trying to hang on for her son, who’d like to follow in the family tradition of growing rice.

“I feel, personally, a lot of pressure to hold onto at minimum our family land that my great-grandfather bought,” she said. “And so when I’m considering what next year looks like, I guess I’ll farm as long as I can without losing our land.”

Raun, the Texas farmer, said the farm aid payment rate for rice growers is fair but won’t make him whole. Unless things change, he said, “there’s going to be a whole lot less rice farming in Texas.”

Topics Trends USA Agribusiness

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Stryker Remains Offline After Cyberattack Linked to Iran Group

Stryker Remains Offline After Cyberattack Linked to Iran Group  Study: AI May Be Tempering Insurer Hiring

Study: AI May Be Tempering Insurer Hiring  Florida House Gives Final Approval to Much-Debated Citizens Clearinghouse Bill

Florida House Gives Final Approval to Much-Debated Citizens Clearinghouse Bill  Travelers Stranded by War Learn Insurance Won’t Cover Flight Cancellations

Travelers Stranded by War Learn Insurance Won’t Cover Flight Cancellations