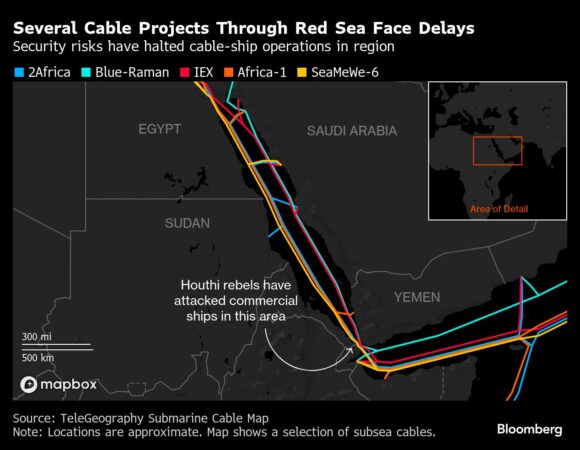

Multiple subsea internet cables slated to run through the Red Sea are yet to complete as planned, as political tensions and heightened security threats have made the route more dangerous and complicated for commercial vessels.

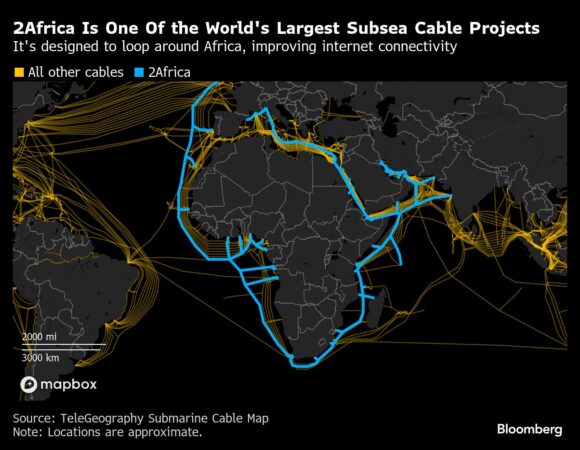

Meta Platforms Inc.’s 2020 plans for 2Africa, a 45,000-kilometer (28,000 mile)subsea cable system, included a map showing how it would loop around the African continent to deliver vital high-speed connectivity. As the company and its partners ready to declare the project complete, a significant portion running through the Red Sea remains unfinished five years on. (Editor’s note: Since this article’s original publication, Bloomberg has added the two graphics below.)

The southern Red Sea segment of 2Africa hasn’t yet been built due to a “range of operational factors, regulatory concerns, and geopolitical risk,” said a spokesperson for Meta, which leads a consortium of telecom companies developing the cable. Other consortium members did not respond to requests for comment.

Progress in the region has also been delayed on the Google-backed Blue-Raman cable, a spokesperson for Alphabet Inc.’s Google said, without providing any further details.

Other cables that have yet to go live through the Red Sea include India-Europe-Xpress, Sea-Me-We 6 and Africa-1. Representatives for telecommunications companies involved in those cables either declined to or did not respond to requests for comment.

The physical, fiber-optic cables that run along seabeds are the fastest and most popular way to transmit internet data across continents. An estimated 400 cables carry more than 95% of global internet traffic. Damage caused by weather or passing ships can trigger widespread internet outages, particularly in less connected regions.

The Red Sea has historically been the most direct and cost-effective route for internet data arteries connecting Europe with Asia and Africa. But construction is complicated by its status as a conflict zone, and the sensitive negotiations requiredby cable operators to obtain permits.

Repeated missile attacks over the past two years in the channel by Iran-backed Houthis, designated as a terrorist organization by the US and its allies, have forced cargo ships on lengthy detours and disrupted the work of specialized ships that lay or repair the cables.

The disruption is throttling the supply of much-needed broadband in under-served countries, keeping prices higher and internet speeds slower for consumers.

The delays also carry financial costs for cable owners and investors, who have already paid suppliers for installation.

“They are not only unable to monetize their investments by sending data over these cables, but they are forced to purchase capacity on alternative cables to meet their near-term requirements,” said Alan Mauldin, research director at telecommunications data firm Telegeography.

The owner of Ireland-based subsea fiber specialist Aqua Comms in January sold the company at a discount, citing problems including the “indefinite delay” to EMIC-1, part of the 2Africa cable, “due to ongoing conflicts in the Red Sea,” according to a filing.

The Houthi-controlled telecommunications ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

Red Sea Geopolitics

The difficulties of operating in the Red Sea have forced technology and telecommunications firms to rethink how they move high volumes of internet traffic around the world.

While cargo ships can divert at relatively short notice around the southern tip of Africa to avoid missile attacks, subsea cables are typically planned years in advance of installation. It is almost impossible to install a cable in the Red Sea without a permit, which involves lengthy negotiations between the various factions controlling the strait. There are also security concerns for the specialized cable ships and their crew, said Mauldin.

Meta’s spokesperson said the company is involved in about 24 projects globally and believes one of the best ways to mitigate the risk of disruption is to diversify connectivity routes.

Telecom and tech companies are now considering alternative overland routes through Bahrain and Saudi Arabia to bypass the Red Sea. Once considered too costly and indirect, these paths are becoming increasingly viable options.

Even a route through Iraq, historically seen as geopolitically risky, has become a possible alternative. Several telecom companies including the UAE’s E&, Qatar’s Ooredoo and Gulf Bridge International have bought capacity on the Silk Route, said Asoz Rashid, chief executive officer of IQ Group, which developed the route.

Other companies involved with the cables are considering applying for a US Treasury Department exemption to engage directly with the sanctioned Houthi-backed government in Sanaa, Yemen, to obtain permits to continue work, according to people familiar with the matter. They asked to remain anonymous as the information is private. They are also considering calling for assistance from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the people said.

The Red Sea corridor is now seen as a “critical, high-risk single point of failure,” Rashid said.

Ultimately, diversifying away from the Red Sea “will lead to much more resilient infrastructure, with a diverse array of connection points from the Middle East and Africa to Europe,” said Mauldin.

Topics Google

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting

World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting  Judge Tosses Buffalo Wild Wings Lawsuit That Has ‘No Meat on Its Bones’

Judge Tosses Buffalo Wild Wings Lawsuit That Has ‘No Meat on Its Bones’  AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers

AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers