When it comes to climate change, there are two Chipotles.

One is the fast-casual burrito chain with a focus on sustainable ingredients, an app that lets customers track the carbon footprint of their orders and a goal to halve its heat-trapping emissions in the next six years to help fix “one of the most pressing issues of our time,” the company says. The other is a key member of the Restaurant Law Center, an industry trade group that is suing and supporting litigation to beat back pivotal climate rules.

Such contradictions are rife among many of the world’s biggest hotel operators and restaurant chains. Marriott and Hilton have pledged to cut their carbon emissions by almost half by 2030, while the parent companies of KFC, Taco Bell and Burger King have made similar climate commitments. But all of these companies are important members of powerful trade associations that have recently filed lawsuits to overturn critical local and state climate rules. The litigation could deter climate action among city and state lawmakers, who have surpassed the gridlocked federal government as the primary drivers of green policies in the U.S.

“A lot of companies have sort of outsourced their climate obstruction to their trade associations,” says Timmons Roberts, professor of environment and society at Brown University. “People have been focused on Exxon and the Koch Brothers, but climate obstruction is really much more complicated, and it’s everywhere.”

This issue has recently leapt to the fore in Colorado, where lawmakers for the state and for Denver enacted rules to slash greenhouse-gas emissions from buildings, including hotels, offices and apartments. Despite being less ambitious than the climate pledges of Marriott International Inc., Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. and others, the rules are now under fire from industry groups like the Colorado Hotel & Lodging Association, where Marriott representatives hold powerful board seats, as well as the Restaurant Law Center.

Chipotle’s press team didn’t respond to numerous messages, while a Marriott spokesperson said in an email that “we do not directly control the actions taken by industry associations or business groups,” and affirmed the company’s climate commitments.

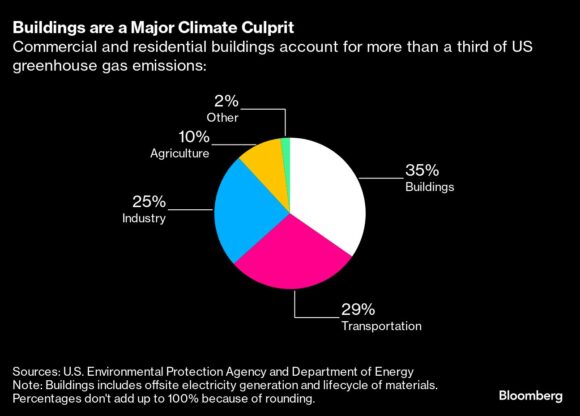

The climate stakes are significant because buildings are an outsized source of emissions. Occupants burn methane gas to heat water and power furnaces, and they gobble up electricity. These structures account for about half of Denver’s climate footprint, and, more broadly, about 35% of heat-trapping emissions in the US.

Buildings are a Major Climate Culprit | Commercial and residential buildings account for more than a third of US greenhouse gas emissions:

Both Denver and Colorado have embraced a new tactic for addressing this. Lawmakers recently enacted building performance standards, which require large structures to become more environmentally friendly. This type of rule was first implemented in Washington, DC, in 2019, and has since spread to 13 states and cities across the US, with nearly three dozen more local governments vowing to follow. But legal challenges, including those filed against Denver and Colorado by the hotel industry and others, could sap this momentum.

“By bringing these lawsuits in a lot of different places…the industry can generate the idea that these are risky, and therefore drive away local governments from doing it,” says Daniel Carpenter-Gold, staff attorney for the Public Health Law Center at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law.

In Denver, the rules require that about 3,000 buildings cut their energy use by an average of 30% by 2030. About a quarter of the city’s buildings already meet the 2030 requirements, while owners of less efficient structures — including the Sheraton Denver Downtown Hotel, which is part of Marriott — may need to slash their energy use by one-third or more.

For both the state and city rules, building operators get to choose how they’ll achieve savings. This could mean deploying LED lighting, installing heat pumps, adding solar panels, or other solutions. In Denver, requirements for most buildings start next year, with warning notices for potential fines — upwards of millions of dollars for laggards — going out by late 2026.

When industry groups, including the Colorado hotel operators, sued to block both the state and city requirements in April, they claimed the rules are preempted by federal energy law that regulates the efficiency of certain appliances. Moreover, the requirements will “cost billions of dollars” and take far more time than has been allotted, according to talking points distributed by the groups.

The hotel association’s board is packed with executives running properties for major hotel chains. The executive committee is chaired by Tony Dunn, who manages the Sheraton in downtown Denver, while its secretary manages the Ritz-Carlton in Denver, which is also part of Marriott. Other board members represent properties from Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. and Hyatt Hotels Corp., which has pledged to cut more than a quarter of its emissions by 2030.

Dunn didn’t respond to messages, but he submitted a declaration supporting the lawsuit that said the rules would force his hotel to “incur significant costs.” That could include at least $100,000 to $200,000 for an energy audit, he wrote, “to identify available options to achieve the building performance standards…and begin the planning process for making material modifications.”

Hilton and Hyatt didn’t respond to messages. Amie Mayhew, president of the Colorado Hotel & Lodging Association, said she couldn’t discuss the matter due to the litigation.

A separate Denver rule, meanwhile, is facing blowback from national trade groups representing major hotel and restaurant chains, including Chipotle, Burger King and Taco Bell. The city, in addition to its building performance standard, recently banned gas-powered furnaces and water heaters in newly constructed large buildings. In some cases, operators of existing large buildings will also be required to install electric equipment when replacing these types of appliances as early as next year.

This would avoid locking in gas-burning equipment that lasts for a couple of decades — and it will shrink emissions as Colorado’s electricity supply gets greener. The state’s last coal plants are expected to close by 2031. And Xcel Energy, the state’s largest utility, has agreed to supply about 80% of its electricity to the state from renewable sources by the end of the decade.

In July, however, industry groups including the Restaurant Law Center, the American Hotel & Lodging Association (whose top board officials include Hilton and Marriott execs), and the National Propane Gas Association (NPGA), filed a lawsuit to overturn Denver’s rules that limit new gas equipment. They similarly argue that federal energy law preempts such local rules; and they warn that this would shrink the number of gas users, thus causing the price of the fossil fuel to spike for remaining customers, including restaurants.

This legal challenge isn’t just about Denver. The gas industry privately hopes the litigation will dissuade other cities from restricting gas appliances, according to a summary of the NPGA’s executive committee meeting in May, which was viewed by Bloomberg Green. In it, the group lamented Colorado’s increasingly ambitious climate rules, saying “it has rapidly turned into a problematic state from a marketplace competitiveness standpoint.” It added that it was monitoring 12 municipalities that are exploring rules to restrict gas and promote electrification. “If this Denver code goes unchallenged and is allowed to stand,” it stated, “there is concern that other Colorado communities…will follow suit.”

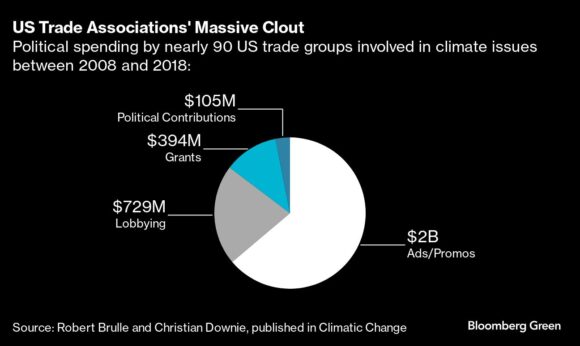

US Trade Associations’ Massive Clout | Political spending by nearly 90 US trade groups involved in climate issues between 2008 and 2018:

The Restaurant Law Center’s role in the lawsuit isn’t new terrain for the nonprofit. Last year, the group filed a legal brief in support of the California Restaurant Association’s litigation against the City of Berkeley, which had enacted the nation’s first ban on gas hookups in new homes and buildings. The restaurant groups eventually prevailed, dealing a sharp setback to climate action as Berkeley and dozens of other cities were forced to scrap rules that halted the expansion of the gas system.

The Restaurant Law Center states on its website that it “gets involved with many cases brought to its attention by its Board of Directors.” That board consists of 12 outside members, a quarter of whom are executives with restaurant companies — Chipotle, Yum! Brands Inc. and Restaurant Brands International Inc. — that trumpet bold climate commitments, including “science-based targets” to reduce their emissions in line with a 1.5C future. Chipotle even unveiled an all-electric kitchen design last year to help it meet its climate targets. “We hold ourselves accountable to reduce the environmental impact of our restaurants,” Laurie Schalow, Chipotle’s head of corporate affairs, said at the time.

Schalow declined to comment. A spokesperson for Restaurant Brands International, the parent company of Burger King, didn’t answer questions about its role in the trade group’s legal efforts, but said in an email that “our focus is on our own commitments to grow a sustainable business,” including cutting its emissions by half by 2030. A spokesman for Yum!, which runs KFC and Taco Bell, also didn’t answer questions about the litigation, but said in an email that the company “remains committed to climate action,” including its science-based targets. Angelo Amador, executive director of the Restaurant Law Center, didn’t respond to several messages.

A spokesman for the American Hotel & Lodging Association didn’t respond to questions about the Denver lawsuit, but said in a statement that the group has “room for a wide range of climate goals and actions within our diverse membership base and are focused on ensuring hotels have the flexibility they need to become more efficient.”

Sarah McLallen, vice president of communications at NPGA, meanwhile, said in an email that her group “strongly believes in energy freedom and consumer choice.” This means consumers should “decide for themselves what energy source is most appropriate,” she said.

For companies to have integrity with their climate claims, activists say they need to be on the same page as the trade groups they fund. That means advocating for green policies inside of the groups and publicly speaking out in favor of legislation when their views differ. When the California Chamber of Commerce, for instance, opposed a state bill last year that would require large businesses to disclose their greenhouse gas emissions, some members of the group, including Salesforce Inc. and Microsoft Corp., broke ranks and embraced the proposal. It eventually prevailed.

“We want companies to use their influence to shift how the trade associations are lobbying,” says Deborah McNamara, executive director of ClimateVoice, a nonprofit that pushes companies to advocate for climate policies. If trade groups can’t be swayed, she adds, companies should stop funding them.

It’s a step that occurs very infrequently. Apple Inc. famously quit the US Chamber of Commerce in 2009 after the group attacked a variety of climate proposals, including a TV spot that lampooned a federal cap-and-trade bill. Five years later, Google’s then-executive chairman accused the American Legislative Exchange Council of “literally lying” about climate change as it cut ties with the group. And, in 2019, Shell Plc departed a group called the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, citing differences over climate policy.

Mostly, though, these differences quietly linger. A report by E&E News earlier this year found at least 37 companies, including Pfizer Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc., reported their own climate policies are at odds with their participation in the US Chamber of Commerce. For some companies, this disconnect has persisted for well over a decade.

“This is one of the biggest problems that we have to solve,” says McNamara of ClimateVoice.

Top photo: A coal-fired power plant in Craig, Colorado. The state’s last coal plants are expected to close by 2031. Photographer: Chet Strange/Bloomberg.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

A 10-Year Wait for Autonomous Vehicles to Impact Insurers, Says Fitch

A 10-Year Wait for Autonomous Vehicles to Impact Insurers, Says Fitch  Fingerprints, Background Checks for Florida Insurance Execs, Directors, Stockholders?

Fingerprints, Background Checks for Florida Insurance Execs, Directors, Stockholders?  ‘Structural Shift’ Occurring in California Surplus Lines

‘Structural Shift’ Occurring in California Surplus Lines  Portugal Deadly Floods Force Evacuations, Collapse Main Highway

Portugal Deadly Floods Force Evacuations, Collapse Main Highway