Workers’ compensation leaders are being urged to move away from thinking primarily about how best to prevent and treat a worker’s physical injury to considering how to help the whole worker.

It’s a daunting assignment given the variety of ways that work may affect the health and well-being of a worker, as well as how many factors other than work can influence a person’s health.

“In general, we don’t do a good job of appreciating the risk that work plays in our lives,” says Dr. Casey Chosewood from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

A job can influence a worker’s health in a number of ways including through its design, wages, stability, benefits, hours, location, training, relationships and environment.

“Work for many people is their main source of benefits. If you’re a Hispanic female without health insurance in this country, you will die a decade sooner than the average woman in this country. But increasingly, we see healthcare benefits being separated from the employment contract,” Chosewood says. “And pensions, forget that, that’s a thing of the past.

“Work is also an important way that we gain social status and gain connections to other people who can be supportive or can be debilitating to our health and well-being.”

One’s job is related to the likelihood of having one of a number of chronic diseases including heart disease, asthma and hearing loss. Work is also related to obesity, diet, smoking, stress, depression, exercise, car accidents, and even life expectancy.

(See: Involuntary Benefits: Security, Time and Obesity)

“While we cannot get rid of every risk factor, and that’s true of all occupational exposures, we can decrease the impact of those by intervening more aggressively and more frequently with health promoting interventions,” according to Chosewood.

“Your lives are dedicated to harm reduction. Add to your portfolio. We need to improve the quality of work so we counterbalance some of the inevitable harms that come from employment,” he said, challenging the audience at this year’s Workers Compensation Research Institute’s annual conference.

Chosewood is director and senior medical officer at NIOSH and an advocate of the Total Worker Health program that is designed to minimize the risks and optimize the health opportunities for workers.

Chosewood recounts the oft-heard genealogy of jobs: “My father had one job for his entire life. I’ve had six jobs in my life. My kids will have six jobs at the same time, right?”

That reflects the feeling that there is a lot about work that is changing.

“There is a shifting of the way that we’re employed, the way work is designed and delivered, the way that we handle the contract that governs how we are paid and the work we do. All of these things are dramatically changing. Work, if you think about it is this paradox of harm and benefit. Work is one of those things where we say, ‘Yeah, having some of this is good for you, but don’t take too much. It can kill you.'”

He believes the Total Worker Health approach is one of the best tools for navigating that “fine line between harm and benefit.”

He wants employers and insurers to “think beyond safety, beyond health promotion and start thinking more comprehensively and promptly about all of the ways work impacts our health.”

Where to Start

There are obviously many jobs that are well -designed, stable, well-paid, safe and contribute positively to a worker’s well-being. But those are not the jobs where Chosewood thinks attention needs to be paid.

Low wage workers and employees in small businesses are the most at risk and where employers and the industry should focus their attention.

Most workplaces have low wage workers. They tend to be workers with more hazardous jobs and thus more likely to be injured, according to NIOSH. They often have little control over their work and are also prone to job insecurity, forced overtime and discrimination. They are at increased risk of job stress and mental health disabilities.

“If your organization wants to intervene, this is where the money is. If you don’t have enough money to intervene in every demographic in your workplace, starting here is going to give you the biggest bang for the buck,” Chosewood said.

The other area that should be on risk managers’ radar is small businesses, which number about 30 million, according to the Small Business Administration. More than a third (33%) of the U.S. workforce is employed in businesses with fewer than 100 employees, and 16% of workers are with businesses with under 20 employees. “If your industry serves smaller employers, this is an area of potential influence,” he said.

According to Chosewood, small firms tend to “struggle to exist in a risky economic environment,” and they often lack sufficient resources for employee training, workplace safety, health initiatives and protective equipment.

Many small businesses do not survive beyond four years, but those that last five years have less than half the annual workplace injury rate as businesses that lasted only two years, according to NIOSH.

Bad, Good and Great

Chosewood sees three types of employers: bad, good and great.

“Bad companies send their workers to work in the morning with 10 fingers and toes and send them home with less at the end of the day,” he says. “That’s a bad company. They’re not following the law. They are asking workers to trade health for wages every day.”

A good company meets its obligations of the law. “Most of your clients out there are probably good companies. They do have their core set of values. This belief that I have to protect these workers and I have to send them home with the same level of health that they arrived with that morning,” he said.

Great companies are the ones that people clamor to work for, the ones that have much better retention, engagement, rating, satisfaction rates and can boast of employees recruiting their friends to work there.

Here’s what great companies do, according to Chosewood:

“The great companies are the ones that do step one. They keep the 10 fingers and toes, but they invest through three Ps of policies, practices and programs in ways to better design work that actually improves the health of that worker. So, the workers don’t go home on the same level of health; they go home at the end of the day with a higher level of health than they arrived with. That’s a lot of money to spend.”

What a great company does is great for workers and their families. It’s great for the communities they live in. But what’s in it for the employer?

Chosewood has the answer:

“Here’s the secret. Those same workers that went home with more health at the end of that day come back to work the next morning with that increased level of health. And that quickly, very quickly according to our research, translates into lower injury risks, to more engagement, to more productivity, to fewer days of absenteeism, to lower healthcare spending over time. That is the secret sauce, the win, win, win of the Total Worker Health approach. So put simply, keep workers safe and invest in the best practices and policies to improve their health.”

The job contract is sometimes as powerful as the actual job when it comes to health of low wage and small business employees, according Chosewood. People who don’t have secure work often face other related risks.

“Workers oftentimes under some employment circumstances may not have appropriate training. They may not have the same access as full time employees to the appropriate personal protective equipment. Their supervisor chain is oftentimes cloudier. This is a significant issue ongoing for the way that we protect our workers,” he said.

Furthermore, hazardous work is often outsourced, leading to a concentration of high entry risk jobs for these workers. This type of work has other side effects. “It tends to isolate, it tends to make vulnerable populations more vulnerable under certain employment conditions,” he said. “So, as we’re thinking about injury reduction, one of the critical things to look at is how is the contract written for workers?”

The TWH Approach

(See: NIOSH Total Worker Health Program)

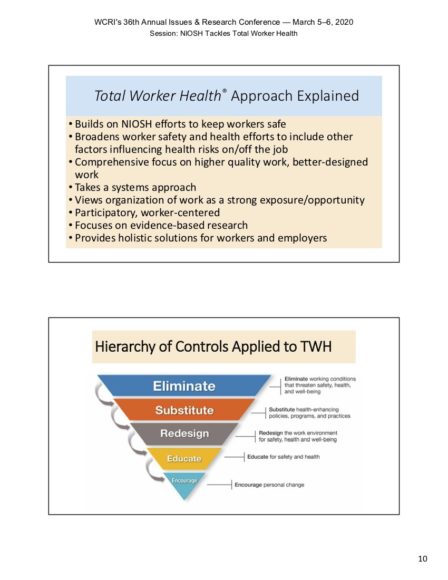

The Total Worker Health approach places top priority on eliminating working conditions that threaten safety, health and well-being. Next, it focuses on substituting health-enhancing policies, programs and practices; third, it looks at redesigning the work environment; fourth, it educates for health and safety; and finally, it encourages personal change.

The Total Worker Health approach broadens worker safety and health efforts to include other factors influencing health risks on and off the job. It stresses a focus on higher quality work and better designed work. But, interestingly, NIOSH does not emphasize the health promotion aspect. It actually minimizes the role of an individual behavior change or health promotion program, according to Chosewood.

“You cannot overcome eight, 10, 12 hours of hazardous work with a ‘lunch and learn’ on diabetes. It’s not going to happen,” he quips. “You have to think more upstream. You have to think about organization level interventions, policy level interventions, population health, really at play here.”

He stressed that workers need a say in the development of the policies, practices and programs, the three Ps. “So, it’s not a ‘we build it, they will come.’ It’s a ‘they build it, they will come,'” he said.

The blending of work and non-work-related issues is key, according to the NIOSH director.

“You don’t leave all of your home issues in the parking lot and come into the office. You bring that with you. And conversely, you don’t leave all of your workplace stressors in the office, you take those home with you. So, employers have a stake in the total health of their workers.”

Everything should be supported by an integrated system. In short, a company’s safety committee should talk to benefits design, and benefits design should talk to health promotion and the EAP and others and their workers.

“All those people should be on one team,” he told the workers’ compensation leaders. “We shouldn’t have an HR team and a safety team. There needs to be a worker well-being approach that integrates all those systems. You’re all after the same thing at the end of the day.”

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

New York Taxi Insurer Failed to Defend Uber in Crash Cases, Judge Says

New York Taxi Insurer Failed to Defend Uber in Crash Cases, Judge Says  Georgia Insurance Law Is About to Get an Upgrade With Multiple Changes

Georgia Insurance Law Is About to Get an Upgrade With Multiple Changes  Lloyd’s Market Engaging With US Government Over Gulf Maritime Plan, Officials Say

Lloyd’s Market Engaging With US Government Over Gulf Maritime Plan, Officials Say  Insurance Gaps Leave Airlines Exposed as Iran Conflict Widens

Insurance Gaps Leave Airlines Exposed as Iran Conflict Widens