Charlie Clarke fell severely ill in late summer 2023 after a swim at Clevedon Marine Lake in southwest England while training for a Triathlon. The next day he collapsed on the street near his home and was taken to the hospital, where after a series of tests he was diagnosed with myocarditis — an inflammation of his heart muscle caused by an infection.

The diagnosis was a shock for Clarke, an otherwise healthy 28-year old designer, and he had to stop training. It took him about six months to do sports again and a whole year to get back to the same level of fitness. Since then, he has been “very cautious” and so far only trained in pools. He pulled out of a triathlon in September on the morning of the event after he learned of a recent sewage spill at the beach where the swim was taking place.

Clarke’s story is one of many showing how severe the impact of Britain’s sewage crisis can be on everyday life. As the weather turns warmer, the swimming season is getting underway, and although spills were supposed to become fewer, they’ve worsened. Untreated sewage entered English waters for a record 3.61 million hours last year — a result of aging infrastructure which sends rain and wastewater from toilets and kitchens through the same pipes and often overflows into rivers and seas.

Read more: UK Water Bosses Face Up to Two Years in Prison for Polluting

The depth of the health problem is still unknown, even as campaigners such as Surfers Against Sewage attempt to track thousands of cases of sewage-related sickness. The issue became a key battleground in last year’s election, with waterways playing an important role in the economic and community life of the island nation. Frustration over their degradation is likely to be even higher this summer after water bills were hiked as much as 47% in April to help curb pollution.

“The fundamental issue is that water companies just waited too long to invest,” said Kevin Grecksch, a social scientist and lecturer in the University of Oxford’s school of geography and the environment. “Now they’re playing a game of catch up, which they can’t win.”

One doctor that Bloomberg spoke to for this story, who asked not to be identified discussing patients publicly, said that sewage-related illnesses have increased since April when it was warm enough for more people to swim in the sea. They said that about one in 10 patients calling the Cornwall-based doctor’s surgery for advice are reporting symptoms related to ingesting sewage and have been in the sea recently.

Efforts to fix the problem have kicked into motion, but they are slow. The UK’s water sector has been stuck in a persistent crisis, with Thames Water Utilities Ltd. — which serves about a quarter of the UK’s population — at the forefront. The company underwent a massive borrowing binge since it was privatized in 1989, but has been accused of allocating little to infrastructure upgrades and more toward investor returns.

Companies in the sector have faced intense political and regulatory scrutiny as a result of the issues. They recently received approval to spend over £11 billion ($14.6 billion) to fix sewage overflows.

“The water sector in England and Wales has seen an unprecedented year of change and progress,” a spokesperson for industry association Water UK said. But “the regulatory system is painfully slow, hugely expensive and ridiculously complicated.”

Whether it’s companies or regulators dragging their feet, the consequences for some parts of the broader public have been life-threatening.

Suzi Finlayson, a 45-year-old who once swam regularly at the southern English Aldwick Beach, became seriously ill around Christmas of 2023. At the hospital she was diagnosed with a blood infection that damaged her heart and eventually required surgery. Finlayson, who has lived by the sea since she was 11 and worked as a life coach, has still not fully recovered and had to close her business because she no longer had the energy to work.

“In a normal day I would walk my two dogs, take care of my children and work the whole day,” she said. “Now after a couple of hours I am exhausted and I am still trying to find a way out of that. I went to hell and back.”

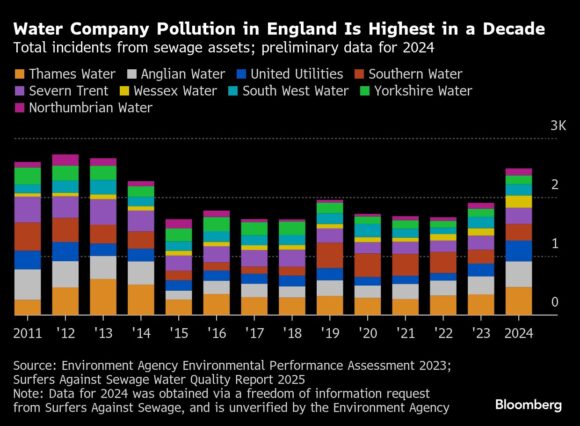

The problem hardly seems to be abating. Water companies in England reported the highest number of pollution incidents in a decade in 2024, according to Surfers Against Sewage. Director of campaigns and communities Dani Jordan said untreated discharges happen throughout the year, even during less rainy months which should in theory see fewer spills. The group’s annual Paddle Out protests to demand an end to sewage pollution will take place next week.

Campaigners and academics say the quality of the data tracking sewage spills is also an issue. Companies and regulators should be looking at the actual volume of what’s going out, instead of counting spills, according to Peter Hammond, a retired professor who has become an environmental activist and tracks data on sewage discharges.

“Sometimes spill monitors say there was a spill when there wasn’t and they miss spills when there were spills,” Hammond said. The data is partially used as the basis for negotiations on water companies’ prices and fines, he said, comparing the process to “a house built on sand.”

Funding and information aren’t the only challenges. Fixing chronic leaks becomes even more tricky with a growing population and climate change, according to Tim Chapman, partner and a member of Boston Consulting Group’s travel, cities and infrastructure practice. He says spending isn’t only needed for water treatment capacity, but along the entire supply chain from materials to workers’ skills. The National Audit Office said recently it would take the water sector 700 years to replace its aging pipelines at current rates, as well as “an unprecedented amount of investment.”

For now, the onus remains largely on individuals to prevent sewage-related illness. Surfers Against Sewage created an app to inform users about local water safety, but there are few official resources, beach closures or event cancellations by authorities to protect swimmers.

Businesses who suffer from the fallout are also left to their own devices, according to David Jarrad, Chief Executive of the Shellfish Association of Great Britain. The shellfish industry has had to spend money on new tank systems and infrastructure to clean their products “because there is too much pollution in our waters.”

“We don’t get any compensation or anything like that,” Jarrad said.

For Miriam Oates, who grew up by the coast of England and spent much time at the beach as the daughter of an oyster farmer, the problem means cutting back on activities she has done her whole life.

The 28-year-old fell seriously ill last summer after meeting a friend for a post-work swim, which is a common thing to do in Cornwall. The next day she experienced severe exhaustion and gastrointestinal issues, symptoms she encountered again a few months later after surfing at the nearby Great Western Beach in Newquay.

“I couldn’t function,” Oates said. “When I got over that bout of sickness, I felt quite anxious about getting in the water again.”

Top photograph: A storm overflow outlet at Bexhill-on-Sea, UK; photo credit: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

Related:

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs

Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs  State Farm Adjuster’s Opinion Does Not Override Policy Exclusion in MS Sewage Backup

State Farm Adjuster’s Opinion Does Not Override Policy Exclusion in MS Sewage Backup  Florida Regulators Crack the Whip on Auto Warranty Firm, Fake Certificates of Insurance

Florida Regulators Crack the Whip on Auto Warranty Firm, Fake Certificates of Insurance  Jury Finds Johnson & Johnson Liable for Cancer in Latest Talc Trial

Jury Finds Johnson & Johnson Liable for Cancer in Latest Talc Trial