When the Washington Commanders’ quarterback Marcus Mariota landed a last-second touchdown pass to clinch victory against the Dallas Cowboys in January, it’s unlikely devastated Cowboys fans were thinking about turf underlay, or the small Dutch town where it’s made.

Privately owned TenCate Grass, based in Nijverdal, about two hours drive east of Amsterdam, engineers artificial grass for gardens, schools and sports grounds, from municipal facilities to the Cowboys’ AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas.

The firm manufactures in 11 countries and distributes turf to customers in more than 60, but around 75% of its sales come from the US. That means it’s exposed to American trade policy, which, since US President Donald Trump took office in January, has been erratic. On so-called “Liberation Day,” April 2, Trump announced a blanket 20% tariff on EU goods coming into the US. That was dropped to 10% while the parties negotiated — during which time, Trump threatened higher rates of 30% and 50%.

Read more: Europe Inc Swerves Trump Trade War ‘Hurricane’ but Laments Higher Tariffs

“What’s going to happen? What is going to be the rate? If the rate is this, what do you do then?” chief executive Michael Vogel lamented on a recent tour of the company’s Netherlands headquarters. “Are you willing to accept some of that price increase? Which essentially is what it is — it’s a tax.”

The European Union finally agreed a trade deal with the US in late July, under which most European products sold in the US will be subject to a 15% tariff. That rate has given European businesses some sense of predictability, but there are still many challenges. There are difficult conversations with American customers about pricing, hard choices to be made about where to invest in the short- and long-term — and a lingering uncertainty over whether the US will stick to the deal while Trump is in the White House.

“I can understand why people are yearning for certainty and I can see why they are interpreting this as a form of certainty, but I just don’t think real certainty is going to be available for the next four years,” Dmitry Grozoubinski, senior trade analyst at Aurora Macro Strategies and a former Australian trade negotiator, said. “There is no analytical framework that survives contact with a US trade policy that is significantly tied into one human being and significantly tied into vibes. So I think they have more certainty than they did before, but no one truly has certainty.”

TenCate’s business shows how integrated global supply chains are, even in relatively niche markets like artificial turf. The company is big, with $2 billion in annual sales, and has four factories in the US — three in Georgia and one in Tennessee — where it employs around 3,000 people. That means it can shield itself from most of the US tariff impact, but not all of it.

Artificial turf needs to perform in all weather conditions, whether it’s being used for lacrosse matches in Boston’s cold winters or American football in a Texas summer. But the polymers that make up the turf tend to shrink and expand with temperature differences. To stop this from happening, TenCate underpins its fields with a complex backing cloth called K 29, which consists of layers of warp-knitted polypropylene. “This backing cloth is critical,” Vogel says, holding up a nondescript piece of white material. “This is the essence. If this is stable, so this doesn’t expand or shrink, then your field will remain stable.”

K 29 is exclusively made in Nijverdal. When Vogel thinks about tariff impact, he’s mostly thinking about how much more it will cost to get the K 29 to factories in America.

How much of that increased price can be passed onto customers isn’t clear. The funding for sports pitches comes from a lot of different sources, both public and private, while the landscaping part of the business — which has been expanding quickly as climate change makes natural grass increasingly hard to grow in some parts of the world — is dependent on consumer confidence. A combination of softening demand, combined with tariff-fuelled price increases, would be particularly concerning for the company.

TenCate is watching “with interest,” the ongoing tension between Canada and the US, Vogel said. The company currently sells into Canada from its US factories. On Aug. 1, Trump increased the tariff rate on some Canadian goods to 35%; Canada has retaliated with tariffs on a limited range of products. Vogel said he hopes relations between the two countries settle into a “good compromise,” but for now, can only wait and see.

Vogel joined TenCate in 2016, and has guided the company through trade disruptions before. In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic sent shipping container rates skyrocketing. That, Vogel said, was “a wake up call for all industries all over the world,” that supply chains were vulnerable to geopolitical disruption.

The difference this time is that Covid was a short-term shock. Customers are more willing to absorb the cost of disruption when they know it’s temporary. Tariffs are likely to be in place for a long time, which might prompt US customers to rethink their sourcing.

The EU’s recent tariff deal with the US was greeted with dismay by some European business leaders who warned the deal risks denting Europe’s competitiveness. For Vogel, the certainty, at least, is welcome. “Happy is not the right word, but it’s a relief that we can move on.” As the rate now seems set in stone, he can take the figure into account and take things from there, he says, instead of wondering “is it going to be 50% or 45% or 15% or what is it going to be?”

Nijverdal has been a hub of textile production and innovation for centuries. TenCate started as a textile company in 1704. “The town name Nijverdal is very well known with all our colleagues in the US. Nijverdal is where lots of these developments are actually being done,” Vogel says, surrounded by humming machines and football goalposts in the company’s research and innovation lab.

Outside in the gray Dutch summer, workers are demolishing TenCate’s old Nijverdal factory to make way for a new, larger one, which should be completed next year.

Tariffs aren’t going to convince the company to shift production of K 29 from Europe to the US, Vogel said. The cost of moving production would be enormous, and TenCate wouldn’t be able to replicate the knowledge base it’s built up in the Netherlands. The machines that make the products can be installed pretty much anywhere, but the expertise is hard to find.

When asked which machine in TenCate’s innovation center is the most important, Vogel gestures to an employee, who is deeply engrossed in running some turf samples through a machine. “It’s Colin,” he said. “You can put the machines anywhere, it’s the people that need to know how to work them.”

In high-tech industries, setting up new manufacturing plants can be expensive, multi-year projects that take decades to pay back. They often rely on tightly-engineered supply chains and highly-skilled workforces. While one of the stated aims of US trade policy is to bring manufacturing jobs to America, the administration’s unconventional approach to negotiations disincentivizes companies from making investments.

The logic that the US has given for its tariffs has shifted depending on the country in focus. The 50% tariff that Trump demanded on Brazilian imports was at least partly motivated by a desire to influence that country’s domestic politics. At times, the government has thrown out eye-wateringly high tariff figures —Trump recently suggested that duties on pharmaceuticals could rise to 250% — which have subsequently been negotiated downwards.

“Nobody’s making decades-long investments on the basis of a policy that changes so fast. You can’t predict it week to week,” Grozoubinski said. “They’re actively telling businesses: ‘Hey, not only might these tariffs be gone six months from now because we are just fundamentally changeable creatures driven by whimsy and caprice, but also we’re actively negotiating — and reducing them is on the table.'”

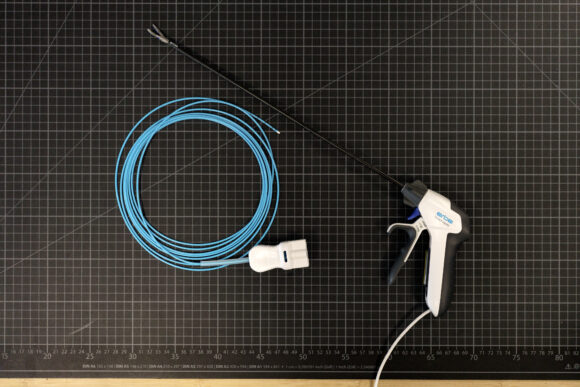

Christian Erbe is the fifth generation of his family to lead Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH. For 174 years, the company has produced medical devices from its headquarters in Tübingen in southwest Germany.

It’s an archetype of the German Mittelstand – the highly-specialized, small-to-medium sized or family-run manufacturing companies that provide the country’s economic backbone. They make up about 99% of the country’s companies and account for roughly 40% of total exports.

Many companies have been struggling with high energy costs, bureaucracy and weak global demand, and the on-again-off-again dynamic of the US’ tariff policy have made it hard to plan ahead, Erbe said. Around 40% of the company’s sales come from America, and while the US-EU deal in July finally brought certainty, the 15% rate on European goods felt more like defeat. “I’m very disappointed,” Erbe said. “That’s not a level playing field, as they say.”

Quitting the US, which is the world’s largest market for medical technology, isn’t an option. Since Trump’s Liberation Day in April, Erbe has been weighing how to respond. Rather than relocating existing production from his home country, he decided to expand operations in the US and direct future investments there. Both moves would ultimately shift capital and know-how away from Germany. In other words: “Trump’s plan is working.”

“The new jobs that will be created are more likely to be in the US than in Germany,” Erbe said. “That’s exactly what Trump wants. But we don’t see any other way to survive here in the long term.”

However, expanding in the US is no quick fix. It will take about two years before Erbe can begin producing newly planned surgical instruments at its Arizona facility, with Erbe citing “enormous” documentation requirements for regulatory approval in the medical sector. Until then, the company will try to pass on tariff-related costs to US customers where possible — a move that Erbe expects to emerge as a broader trend, which will lead to “rude awakenings and unrest among the population” in the US.

To pay for the tariffs, Erbe Elektromedizin will need to divert millions of dollars that it would normally have invested in research and development. “We can’t just nod and say ‘OK, no problem, we’ll make a little less profit’,” Erbe said. “We have to make cuts somewhere. And that naturally has an impact on our ability to innovate.”

If other companies in the Mittelstand make similar calculations, it could erode Germany’s position as a high-tech manufacturing hub, said Erbe, who’s also the chairman of the committee for the industrial healthcare economy at the German industry lobby BDI.

“In Germany, we don’t differentiate ourselves by offering the lowest prices. That’s mainly left to our Chinese colleagues,” he said. “Instead, we differentiate ourselves through innovation. And if we are held back because we simply no longer have the financial resources to continue investing so heavily in this area, then I believe it will become increasingly difficult for us.”

While European countries remain the most important export destinations for Germany’s small- and medium-sized companies, one in six companies does business in the US, which, according to a report by state-owned development bank KfW, is the most important market outside Europe. More than 40% of the over 3,000 firms surveyed expected negative effects from Trump’s policies – and that was in January, before Trump’s tariff announcements.

Not every company has the flexibility to shift production to the US. Moritz Hartenstein, CEO of AKB Antriebstechnik GmbH, a roughly 50-person firm that builds steel gearboxes for rail and food-processing industries, currently sees no way to grow across the Atlantic. The company generates between 10% and 30% of its revenue in the US, and had hoped to grow in the market. But with tariff-related costs — including 50% duties on steel — expansion has stalled. “No US customer is ready to grow with us amid the current uncertainty,” Hartenstein said. “We’re seeing the opposite of what the tariff policy is meant to achieve.”

However, the Mittelstand has typically been good at adapting to changing international circumstances, according to Nadine Kammerlander, a professor at WHU Otto Beisheim School of Management. Family businesses often have relatively simple management structures and can make decisions quickly. “That is a huge advantage in a situation as volatile as the one we are currently in,” she said. “You simply have to exploit this advantage.”

“This situation will separate the wheat from the chaff in the German Mittelstand landscape,” Kammerlander said. “Those who sell products into the US – which is only a fraction – will need to think how they can enter into good partnerships. Others may look at other parts of the world instead, to South America or Asia, for example.”

Europe’s largest private forest owner, SCA, has been turning trees into timber, pulp and paper and other wood products for nearly a century. Based in Sundsvall in central Sweden, the company controls more than 2.5 million hectares of forest across northern Sweden and the Baltics. Eighty percent of everything it produces is exported; 10% of all of its sales go to the US.

“At the start of 2025, the market outlook was very positive,” CEO Ulf Larsson told Bloomberg News in an interview. “But then came Liberation Day, and everything came to a halt.”

Wood products were one of the few EU goods that were exempted from the first phase of interim tariffs that followed the Rose Garden event, but pulp and paper were affected. The scale of the levies was significant, but not unexpected, Larsson said, and the company had to respond pragmatically.

“I would say that nothing coming out of the US right now is surprising,” he said. “From a company perspective you can’t just go around and be worried by the tariffs. You have to focus on the things you can control.”

During the spring and summer, the tariffs have not only driven up costs but also reshaped market dynamics. While EU wood products were exempt in the tariffs announced on Liberation day, Canadian exports faced restrictions. The reverse was true for pulp and paper. “It caused a skewed competition in the market,” he said. “Of course we would rather have no tariffs at all but if there has to be, we would at least prefer a level playing field.”

It’s clear, Larsson said, that the Trump administration wants sawmills to be built in the southern US, and for operations to relocate from Canada to America. But, he said, that can’t happen quickly. “It’s a long process before you can start production with a new pulp or paper machine, it takes several years.” That means that the main impact of the tariffs in the US will be “significant inflation,” Larsson said.

For the rest of the market, the uncertainty brought on by constantly changing narratives and ongoing negotiations has been more disruptive than the tariffs themselves. “After the discussions started in April we have noticed a more cautious market in several ways,” he said, adding that “companies are making investments more carefully and the will to consume among the general population is lower.”

Many of SCA’s US customers have longstanding relationships with the company. While its clients are sensitive to prices, they also care about having security of supply. “You don’t just break old customer relations when there is still so much uncertainty, both sides have been committed to preserving a strategic relationship,” Larsson said. “We were able to negotiate a shared solution fairly quickly. In many cases, we agreed to split the tariff burden in half, in a rather brotherly fashion.”

However, he warned that the fraternal spirit does have its limits. “If EU tariffs were to rise to, say, 30%, while other markets got lower tariffs, I suspect our customers would be forced to look elsewhere.”

Top photograph: A worker operates machinery at the Tunadal sawmill operated by SCA AB — a timber, pulp and paper manufacturer — outside Sundsvall, Sweden, on Friday, Jan. 24, 2025. Photo credit: Mats Andersson/Bloomberg

Topics Europe

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Judge Awards Applied Systems Preliminary Injunction Against Comulate

Judge Awards Applied Systems Preliminary Injunction Against Comulate  AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers

AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers  World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting

World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting  Trump’s EPA Rollbacks Will Reverberate for ‘Decades’

Trump’s EPA Rollbacks Will Reverberate for ‘Decades’