Two years ago, extreme rainfall inundated Hong Kong, turning roads into raging rapids, submerging cars and flooding malls, making it one of the city’s most costly weather events ever. When another round of record-breaking rains drenched the city last month, the damage and disruption were comparatively minimal.

“I was looking outside the window, seeing the rain coming down, and I was expecting way more impact than I saw afterward,” said Andreas Prein, a weather expert who was in town for a forum on extreme rainfall the same week of the deluge. Other overseas attendees also remarked on how quickly Hong Kong returned to business-as-normal: they gathered for drinks downtown within a couple hours of the rains subsiding.

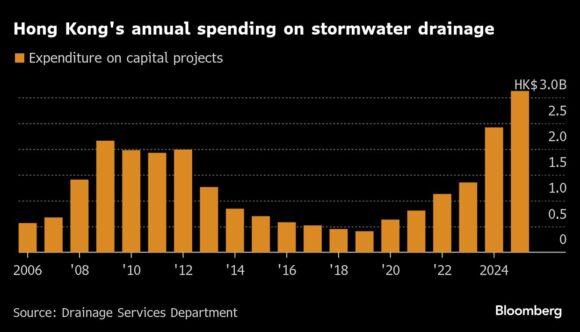

The severe storm notched the highest-ever August daily rainfall total, but it was also up against the city’s sharpened flood management strategy: In the past two years, Hong Kong has more than doubled its annual spending on stormwater drainage to an estimated HK$3.17 billion ($407 million) to address the evolving threat from extreme rains turbocharged by a warming climate.

Other regions have also spent handsomely in their quest to tame stormwaters. Tokyo boasts a world-class flood defense system, Singapore has splashed out on drainage infrastructure, and the Netherlands continues to rely on its network of barriers, dams and wind-powered pumps. But globally, work on climate-proofing has slowed and the gap between required and needed adaptation finance is at least $187 billion a year, according to the United Nations.

For now, billions in investments in sprawling infrastructure in Hong Kong have kept the full wrath of natural disasters in check. That vital but little-known work began decades earlier, long before climate risks entered the public consciousness. Much of Hong Kong is densely packed and perched on, or built at the foot of, steep slopes. The city averages 2,400 millimeters (94.5 inches) of precipitation annually — nearly double what New York City gets — and tropical rain is notoriously hard to predict. As a coastal city, storm surges and rising sea levels put additional stress on its drains.

This combination of factors “is quite unique to Hong Kong,” said Huan-Feng Duan, professor of hydraulics and water resources at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. “The very fast flooding issue means it requires a very high standard of research and also engineering.”

Now, ever-higher temperatures are risking more intense rains, requiring more improvements to Hong Kong’s extreme-weather response.

Driving that effort is the Drainage Services Department, which oversees some 2,800 kilometers (1,700 miles)of stormwater drains — more than the length of the city’s public roads. In the nearly four decades since its establishment, the DSD has invested over HK$32 billion in drainage works to reduce flooding impact. That’s no longer enough.

“The extremely heavy rainfall of 2023 was a wake-up call for us. And we also learned a lesson: it confirmed our thinking that we cannot only rely on adaptation,” said Ringo Mok, director of the DSD. “We have to implement many different measures at once.”

While large-scale engineering projects will still form the “first line of defense” against inundations — the department currently has HK$17.1 billion budgeted for 15 stormwater drainage projects — temporary and non-structural measures will be crucial for the city’s resilience, Mok said.

To that end, the drainage department has expanded its flood-fighting tactics over the past two years. It has identified some 240 blockage-prone drains citywide, and more than doubled the number of emergency response teams to rapidly unclog them when heavy rainfall hits. For better monitoring, it has installed 100 battery-powered flood monitoring sensors citywide that can ping instant alerts, and plans to gradually expand that network. It is also working with academics to develop a machine learning model trained to spot flooding from CCTV images. And it has procured nine mobile pumping machines to quickly clear major blockages.

The approach seems to be bearing fruit, Mok said: All reported floods last year were fully cleared in under two hours.

The DSD is “an unsexy department with a compelling story, especially today in light of climate change,” said Christine Loh, chief development strategist at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and formerly the city’s undersecretary for the environment.

The private sector is stepping up its game, too. Real estate investor Link REIT got a rude shock when the September 2023 deluge flooded one of its malls. It wasn’t that the company had ignored potential hazards — it had recently completed an assessment of flood and heat risks at each of its 150-plus properties. But the mall that ended up with the worst flood damage had never been flagged by its risk models.

“Was it that the model failed, or were we dealing with something different?” said Calvin Kwan, managing director of sustainability and risk governance at Link. “The answer is we were dealing with a whole confluence of worst case situations.”

The risk models had failed to simulate the perfect storm of events: record-breaking rain, a subway station’s flood gate diverting floodwater into the mall and muddy runoff from a construction site nearby. Shops in the mall’s basement level were submerged under 3 meters (10 feet) of water, shutting the entire floor for nearly two months and resulting in millions in insurance claims.

Link realized that its risk models can’t look at an asset in isolation — they must account for changes in the surrounding environment that can create new hazards. It took steps to reduce those risks, including putting up new flood gates, installing real-time flooding sensors and redesigning drainage covers for higher efficiency. All told, Link has spent HK$8 million on flood measures in the past two years, compared to the estimated HK$500,000 in the three to five years prior, according to Kwan.

Railway operator MTR Corp. also learned lessons from the downpour two years ago. It has installed flooding sensors at more than 30 high-risk station exits and entrances since then, and now has a protocol to put up flood boards and activate flood gates when the Hong Kong Observatory hoists its most severe rainstorm warning signal, according to a spokesperson.

Ultimately, even the best flood defense system will fail. The challenge for governments is communicating openly that things will go wrong, while still encouraging the public to assess their own flood risk exposures and take steps to mitigate damages, said Bas Kolen, director of research and development at the Dutch flood risk consultancy HKV lijn in water.

“It’s a challenge for the government to say that we cannot prepare for everything. Of course they like to say that you are safe, but everybody knows that something can go wrong,” he said. “That’s not failure. It’s just to be clear what you can expect.”

Top photograph: A pedestrian in floodwaters during heavy rain in Hong Kong in 2023. Photo credit: Justin Chin/Bloomberg

Topics Flood Climate Change

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Judge Tosses Buffalo Wild Wings Lawsuit That Has ‘No Meat on Its Bones’

Judge Tosses Buffalo Wild Wings Lawsuit That Has ‘No Meat on Its Bones’  Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs

Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs  Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance

Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance  Experian Launches Insurance Marketplace App on ChatGPT

Experian Launches Insurance Marketplace App on ChatGPT