Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina swamped parts of Louisiana and Mississippi, the property insurance sector is better prepared for another catastrophic storm and the litigation that may follow, according to industry leaders.

They point to tighter insurance policy language and better hurricane-loss models. In addition, flood and wind mitigation efforts, new litigation defense techniques, and tort reforms bolster the insurance system, even as storms threaten to gain in strength and frequency.

The next Katrina will likely mean even greater losses. Rising and warming seas can produce stronger storms and more invasive storm surge. Soaring property values, continued development in coastal areas, and likely cuts to funding for weather forecasting and federal disaster relief programs contribute to the risk of tremendous loss.

The next Katrina will likely mean even greater losses. Rising and warming seas can produce stronger storms and more invasive storm surge. Soaring property values, continued development in coastal areas, and likely cuts to funding for weather forecasting and federal disaster relief programs contribute to the risk of tremendous loss.

“As the Gulf continues to warm, the potential for major hurricanes making landfall along the Gulf Coast will increase as well,” Mark Bove, meteorologist and natural catastrophe solutions manager, wrote in a recent report for Munich Re. “Post-Katrina upgrades have made New Orleans’ flood defense systems more resilient, but its effectiveness will erode over time due to subsidence and sea level rise.”

Loss Modeling and Data

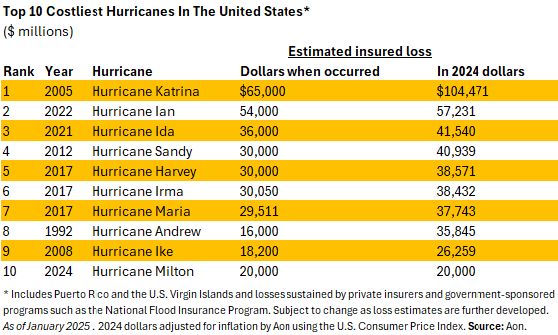

Katrina made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005 to produce what remains the costliest hurricane in the U.S., but insurers today have access to much better data and hurricane loss models—partly because Katrina exposed a big blind spot.

Katrina “really revealed the importance of exposure data quality, which at the time was really lacking, particularly on commercial properties,” said Karen Clark, co-founder and CEO of Karen Clark & Co., one of the most respected hurricane-loss modeling and estimating firms.

Floating casinos on the Mississippi coast in 2005, for example, were geo-coded as hotels, Clark noted. Insurers calculated the risk as if they were land-based structures. But with Katrina’s massive, 25-foot storm surge, those casinos sustained major losses in the storm.

Many insurance carriers at the time were not basing potential loss amounts on exposure data, only on premium data, Clark pointed out. Today, modeling uses extremely high-resolution imaging and data, along with powerful computing, to estimate damage to individual properties. Information on homes is almost iron-clad, with aerial and satellite images showing roof condition, add-on structures, and more, she noted.

During Katrina, many in the industry were surprised by the extent of damage to business property. While some high-rise structures were considered safe from collapse and from some flooding, many buildings in the path of the storm saw damage to windows, facades and roofs, leading to water intrusion that proved to be expensive for insurers, Clark said.

Even today, information on the true value of commercial properties lags well behind that for homes. That’s largely due to how insurance brokers set values and report data for modeling, often underestimating replacement values, Clark said.

“It would be fair to say it’s a little bit of conundrum,” she said in a recent interview with Insurance Journal. “The values of those locations are understated. If the data quality goes up, that means your values go up, which means your premium goes up. So there’s a built-in disincentive to provide high-quality data.”

Robert Hartwig, associate professor of finance and director of the Risk and Uncertainty Management Center at the University of South Carolina, agreed that some brokers tend to understate values of commercial structures, partly to keep from scaring clients off with higher premiums. But he said, overall, the data and the modeling of storms has improved drastically in 20 years.

“In 2025 the level of sophistication that we have in managing major catastrophe risks makes 2005 look like the medieval period,” Hartwig said in a recent interview with AM Best TV.

Building Codes and Mitigation

When Katrina struck, Louisiana and Mississippi had no state-wide building codes. Like a number of states outside of Florida, they relied on local ordinances based on regional or international standards. Today, more states have stronger building requirements and wind-mitigation grant programs. But the progress has been spotty at best, said Michael Newman, general counsel for the Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS).

Louisiana took three years after Katrina to adopt a statewide code, and then failed to update it until recently, he said.

“Only now is Louisiana really leaning into resilience with an updated code, with a fortified grant program, and with other financial incentives for resilience,” Newman said.

Alabama, a state that has seen its share of storms, has led the country in resilience efforts. Two coastal counties there have adopted a building code supplement based on the IBHS FORTIFIED standard, which has become the gold standard for wind-resistant structures, and is catching on nationwide.

Some areas, including New Orleans – with the rebuilding of levees and pumps – have benefitted from government intervention. The infrastructure has withstood a number of storms since Katrina, Hartwig noted.

Still, other vulnerable communities need to do much more, industry veterans said. Mississippi, for example, has yet to adopt a statewide building code, and has allowed local governments to opt out of stronger building practices, Newman said. The state lags far behind others in promoting resilient construction techniques.

“It’s worth noting this continues to be a really pressing need,” Newman said.

Communities must also do a better job with flood mitigation while minimizing coastal development and requiring elevated structures, Hartwig argued.

A few areas are belatedly moving in that direction. In Charleston, South Carolina, for example, city leaders recently took a major step toward building a seawall that was discussed for years.

“The big thing now is mitigating the risk,” Clark said. “The risk is there so we have to adapt. We have to mitigate.”

Claims Litigation and Policy Language

Katrina became just as famous for the intense level of claims litigation that followed the catastrophic destruction. Plaintiffs’ lawyers in Mississippi and beyond filed thousands of lawsuits against insurers, many of which had denied property insurance claims because much of the damage was due to storm surge and floodwaters – perils not included in standard homeowners insurance policies.

Policyholder attorneys argued that without the hurricane winds, the waves and surge would not have formed. Some of the largest U.S. insurers ended up settling hundreds of claims. In one batch of claims in Mississippi, from 640 property owners, State Farm Insurance settled for $89 million.

In the years that followed, insurers tightened policy language to clear up any alleged ambiguity in exclusions, according to sources.

When Superstorm Sandy hit seven years later in New Jersey and New York, plaintiffs’ firms tried a similar, “wind-driven-water” attack but were largely shut down by courts citing clear policy language, Hartwig said.

Not every insurer took note. Appellate courts have ruled in several non-Katrina cases in recent years that some insurance policies continue to contain ambiguous wording, resulting in awards to insureds.

One policyholder attorney who was involved in commercial litigation following Katrina told Insurance Journal that after the storm, and in more recent cases, insurers have tried new techniques to avoid claims payouts. Insureds, likewise, have attempted some new tactics.

Katrina resulted in thousands of business interruption insurance claims from Louisiana and Mississippi companies, explained John Shugrue, partner with the Insurance Recovery Group at law firm Reed Smith. In some cases, insurers argued that claims should be minimized because the business remained accessible after the storm, he said.

In other cases, carriers contended that a payout should be limited because a business’ competitors also were closed after the storm, limiting losses to the policyholder. In another case, a casino policyholder used a similar argument – that because it reopened sooner than others, it should be afforded indemnity based on its stronger sales performance after Katrina. Courts rejected both arguments.

Future Katrinas

Overall, the property insurance industry is well-prepared for another Katrina-like storm, or even worse, the industry experts said. By way of comparison, Hurricane Ian struck southwest Florida in 2022, producing an estimated $60 billion in insured losses. Yet only one carrier faced insolvency, and much of the red ink for that insurer had already come from mounting claims litigation expenses. Florida lawmakers approved landmark reform measures later that year, which appear to have greatly reduced lawsuits and loss adjustment expenses for insurers in the state.

“So, 20 years after Katrina, we have to be proud of what the industry has done, with innovation in the academic and government sectors in understanding and being able to quantify and price insurance, to be able to price this type of cat risk,” Hartwig told AM Best.

“I do believe the industry can handle a loss of Katrina’s size,” Karen Clark added. “Would it cause some disruption in the market? Probably. But with increasing property values, it wouldn’t be a surprise.”

The greater risk for catastrophic losses to the industry will likely come from not one big storm, but from several intense events in one year, Hartwig explained. And it’s not just hurricanes, but severe convective storms that are on track to cause heavy losses in the near future, data suggest.

The good news is that losses from climate change, despite multiple warnings from scientists, will likely be affordable for the U.S. insurance system, Clark argued.

“Once you quantify for climate change, it’s not that scary,” Clark said. That viewpoint is explored in KCC’s recent whitepaper, “Executive Guide to Climate Change Impacts on Insured Losses in the US,” available on the KCC website.

The name Katrina, by the way, will never be used for another hurricane. While most hurricane names are recycled every six years, the Katrina name was retired by the World Meteorological Organization shortly after the deadly storm made landfall.

See the Insurance Information Institute’s Katrina Fact Sheet here.

Top Photo: Members of the Louisiana Recovery Authority tour New Orleans’ hurricane-ravaged Lower 9th Ward shortly after Hurricane Katrina. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, File)

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

CFC Owners Said to Tap Banks for Sale, IPO of £5 Billion Insurer

CFC Owners Said to Tap Banks for Sale, IPO of £5 Billion Insurer  Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears  Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles

Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles